Imagine you’re walking down a busy street when someone suddenly collapses on the sidewalk. You glance around. Dozens of other people are standing nearby, some looking concerned, but no one is stepping forward. Strangely, you feel hesitant to act. Maybe you tell yourself someone else will do it. Maybe you think you’re not qualified. But deep down, you feel frozen.

This reaction is known as the bystander effect — a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help someone in need when others are present. It’s a paradox of human behavior: the more people who are around, the less likely each person is to intervene.

The bystander effect challenges the way we see ourselves. Most of us believe we would step up in an emergency. But studies and real-world events show that we’re far more passive when others are watching — and it has everything to do with the subtle pressures of group psychology.

The Famous Case That Started It All: Kitty Genovese

The bystander effect entered public awareness in 1964, following the tragic murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens, New York. As the story was reported, Genovese was attacked outside her apartment building while 38 witnesses supposedly watched or heard her cries for help but did nothing.

The shocking details — later somewhat exaggerated by the media — sparked outrage and soul-searching. Why would so many people fail to act during a violent crime? Were they apathetic? Cold? Or was something deeper at work?

Psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané decided to investigate. Their experiments revealed that it wasn’t necessarily cruelty or indifference at play — but rather, diffusion of responsibility and social influence. This insight formed the foundation of what we now call the bystander effect.

The Psychology of the Bystander Effect

The bystander effect is driven by several overlapping psychological forces:

Diffusion of Responsibility

When you’re alone and see someone in trouble, you know that you are the only one who can help. But when there are many people around, the sense of personal responsibility gets watered down. Each person assumes someone else will handle it — or already has.

This diffusion of responsibility means that the presence of others actually decreases the likelihood of action. The responsibility is spread so thin that no one feels a strong need to step in.

Social Influence and Pluralistic Ignorance

Humans are deeply social creatures. We look to others for cues on how to behave, especially in ambiguous situations.

If you see a crowd of people who appear calm during an emergency, you may assume nothing is wrong — even if your instincts say otherwise. This phenomenon, known as pluralistic ignorance, causes everyone to misread the situation because everyone is looking at everyone else for guidance.

Fear of Judgment

People also fear making mistakes in front of others. What if you step in and it turns out nothing is wrong? What if you embarrass yourself? The fear of negative evaluation can be strong enough to paralyze action, especially in public settings.

The Ambiguity Factor

Emergencies are often unclear. Is someone lying down because they fainted, or are they just resting? Is that couple fighting, or just having a heated argument? When the situation isn’t black and white, people are far less likely to intervene.

Classic Experiments That Exposed the Bystander Effect

The research of Latané and Darley in the late 1960s provided some of the most striking evidence of the bystander effect.

The Smoke-Filled Room Study

In one experiment, participants were placed in a room to fill out a questionnaire. Soon, smoke began seeping into the room through a vent. When participants were alone, 75% reported the smoke within minutes. But when they were with others who did nothing, only 10% spoke up. Most people stayed silent, assuming that if no one else was reacting, it must not be an emergency.

The Seizure Experiment

In another study, participants were told they were part of a group discussion over intercom. During the session, one participant (an actor) pretended to have a seizure. When participants thought they were the only person who could help, 85% took action quickly. But when they believed others were also listening, only 31% responded.

These studies confirmed that the more people present, the less likely any one person will intervene — a finding replicated in countless experiments since.

Real-Life Examples of the Bystander Effect

The bystander effect isn’t just a lab finding. It shows up in real-world situations all the time:

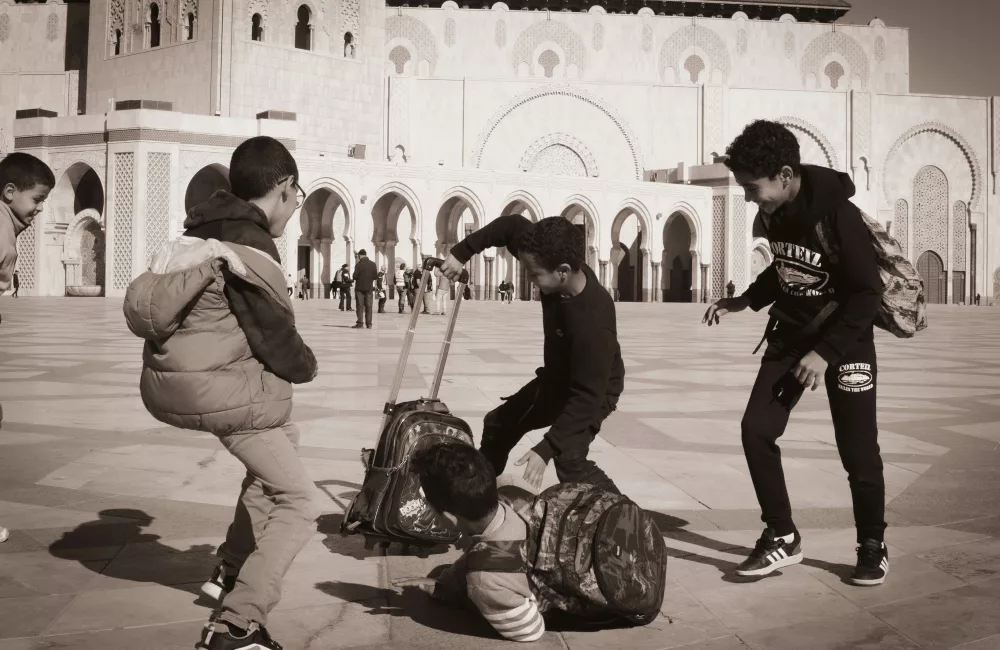

- Public altercations: People are less likely to step in during fights if others are watching, assuming someone else will break it up.

- Medical emergencies: Bystanders often hesitate to perform CPR, especially in crowded places, because they assume someone more qualified will do it.

- Street harassment: Victims of harassment or bullying often report that bystanders remain passive, even when multiple witnesses are present.

Perhaps the most chilling examples come from modern surveillance footage, where we can literally see dozens of people walking past someone in distress — not because they don’t care, but because they’re trapped by group dynamics.

Why Does It Happen More in Cities?

Urban environments are prime breeding grounds for the bystander effect. In large cities, people are constantly surrounded by strangers. This anonymity increases diffusion of responsibility — when you’re one of a hundred faces in a crowd, it’s easy to think, “Someone else will deal with it.”

In rural areas or small towns, people are more likely to know each other or feel a stronger sense of community. That social connection reduces the bystander effect, because personal accountability is higher.

How to Overcome the Bystander Effect

The bystander effect isn’t inevitable. There are proven strategies to override this psychological trap.

1. Recognize It in Yourself

The first step is simply knowing that the bystander effect exists. If you feel hesitant to act in a crowd, ask yourself:

Am I waiting for someone else to do something?

What if everyone else is thinking the same thing?

Just recognizing the pattern can snap you out of paralysis.

2. Take Responsibility

If you see someone in trouble, assume that you are the one who needs to help. Don’t wait for permission or reassurance. Even a small action — calling emergency services, asking “Are you okay?” — can make a difference.

3. Give Direct Instructions

If you’re in an emergency and need help, don’t shout into a crowd. Instead, point to someone and say, “You, in the blue shirt — call 911.” This eliminates the diffusion of responsibility and makes action more likely.

4. Educate Others

Awareness campaigns and first aid training programs often include information about the bystander effect. The more people understand it, the less likely they are to fall victim to it.

The Bystander Effect in the Digital Age

You might think the internet would eliminate the bystander effect — after all, anyone can help from behind a screen. But online spaces have their own version of this phenomenon.

When a person posts about being in danger or needing help, people often scroll past, assuming someone else will comment, share, or offer support. This is called online bystander apathy. In group chats, social media threads, or forums, responsibility gets diffused just like it does on a busy street.

On the flip side, the digital world can also amplify positive bystander behavior. Viral rescue campaigns and crowdfunding efforts show that when someone takes the first step, others quickly follow.

Does the Bystander Effect Mean We’re Selfish?

Not necessarily. The bystander effect isn’t about cruelty — it’s about confusion and social dynamics. In many cases, people genuinely want to help but are frozen by uncertainty.

Interestingly, when people are alone, they are far more likely to help than when they are in groups. This shows that our instincts to help are strong — they just get suppressed in social contexts.

Situations That Reduce the Bystander Effect

Research shows that certain factors make people more likely to intervene, even in groups:

- Clear emergencies: If the danger is obvious (like a fire), bystander paralysis drops.

- Direct requests for help: When a victim asks one person directly, they almost always respond.

- Perceived responsibility: People trained in first aid or emergency response feel a stronger duty to act.

- Cultural values: Societies with strong community norms or collectivist values tend to have lower bystander apathy.

Lessons from Tragedies

High-profile cases, from violent assaults to public accidents, continue to remind us of the bystander effect’s power. But they also teach us that one person’s action can break the spell. When even a single person steps forward, others are far more likely to follow.

In emergencies, the crowd isn’t heartless — it’s waiting for a leader.

Conclusion: Be the First Mover

The bystander effect shows us a strange truth: the presence of others can make us less human — less likely to help, less willing to act. But awareness is a powerful antidote.

If you remember one thing, let it be this: you are the someone. Don’t assume others will step in. Don’t wait for permission. If you see someone in trouble, act — even if all you can do is call for help or speak up.