Exaggeration is a fascinating quirk of human memory that most of us experience at some point. We might do it intentionally for storytelling flair, or it might happen accidentally because our brains have a peculiar way of recalling past events. This subtle enhancement of memories is more than just a habit—it’s a clever trick our brains use to differentiate between similar experiences. An intriguing study conducted by neuroscientists from the University of Oregon and New York University sheds light on this phenomenon. They propose that exaggeration isn’t just a random occurrence but a strategic method our brains employ. It’s like our mental filing system uses bold highlights to make certain memories stand out, particularly when it comes to distinguishing between those that are quite similar.

The Science of Memory Exaggeration

Imagine the time you caught a glimpse of a spider in your room as a child. In your mind, that spider might have seemed enormous, even though, in reality, it was an average size. This exaggeration is not merely a distortion but a mechanism of memory enhancement. Our brains stimulate specific perceptions, boosting the details that make one memory distinct from another.

Experiment Insights

Researchers explored this by conducting an experiment with 29 participants. Over two days, these individuals were shown various images and asked to remember combinations of faces with objects, like umbrellas differing slightly in color. Their ability to recall these combinations improved on the second day, which aligns with the natural learning process. However, the critical finding was how their brains exaggerated color differences to aid memory recall. This strategy allowed them to better remember the right combinations, even if the colors didn’t quite match reality.

The researchers used fMRI scanners to observe brain activity. These scans showed distinct patterns when subjects exaggerated differences between objects. The variations in brain activity were more pronounced, suggesting that exaggeration helps reinforce memory retention.

Neurological Mechanisms Behind Exaggeration

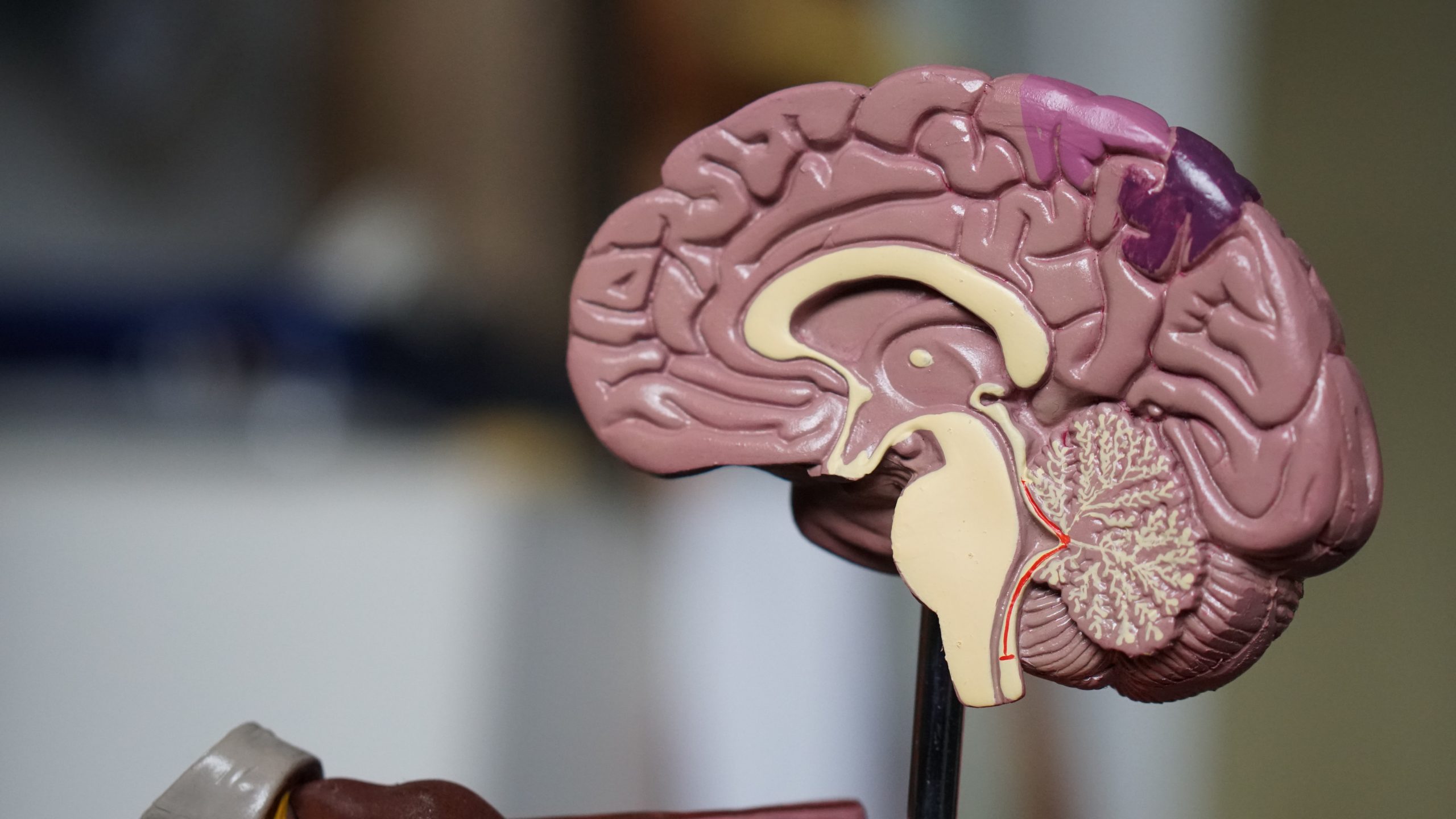

Delving deeper into the neurological underpinnings, it’s fascinating to note how specific regions of the brain, like the hippocampus, play a pivotal role. This brain area is essential for memory formation and retrieval. When we exaggerate, there’s increased activity in the hippocampus, indicating its involvement in amplifying memories. This heightened activity could be why exaggerated memories often feel more vivid and real.

Practical Implications of Memory Exaggeration

This research not only enhances our understanding of memory but also has practical implications. Considering how our brains operate, we can adopt strategies to improve memory retention in daily life.

Tips for Enhancing Memory

- Use Mnemonics: Creating vivid, exaggerated mental images or acronyms can help remember complex information. For instance, to remember a shopping list, visualize a giant loaf of bread smashing through a wall instead of just a loaf of bread.

- Example: For a list including milk, eggs, and cheese, picture a colossal milk carton juggling gigantic eggs while wearing a cheese hat.

- Chunking Information: Break down information into smaller, exaggerated chunks. For example, when trying to remember a phone number, envision enormous numbers dancing around in a silly sequence.

- Practical Application: If the number is 867-5309, imagine the number 8 as a huge snowman, the 6 as a spinning top, and so on, each with exaggerated characteristics.

- Storytelling: Turn facts and figures into exaggerated stories. If you need to remember historical dates, imagine a dramatic scene from that era, complete with exaggerated characters.

- Example: To recall the signing of the Declaration of Independence, picture a giant quill that sparks fireworks with each signature.

- Association: Link new information to something exaggerated you already know. If learning a new language, associate new words with exaggerated images or experiences.

- Illustration: For the French word “chat” (cat), visualize a giant cat chatting endlessly with a beret on its head.

The Role of Exaggeration in Everyday Life

Beyond scientific studies, we encounter exaggeration in various aspects of daily life. From the stories we tell to the way we perceive events, exaggeration plays a role in shaping our reality.

Storytelling and Exaggeration

Storytelling is a perfect example of how we naturally use exaggeration. Whether it’s recounting a thrilling adventure or a humorous incident, we often embellish details to make the story more engaging. This isn’t just for entertainment—it’s a way to make the story more memorable for both the storyteller and the audience.

Consider the classic fish tale. Your uncle might swear that the fish he caught was as big as a car. While this is unlikely, the exaggerated detail makes the story more vivid and easier to recall. This technique is deeply rooted in human culture, enhancing our ability to pass down knowledge and experiences.

Exaggeration in Marketing and Media

Exaggeration is also a powerful tool in marketing and media. Advertisers often use hyperbole to grab attention and make products or services more appealing. Think about car commercials that depict vehicles performing impossible feats. These exaggerations create memorable impressions, influencing consumer behavior.

Everyday Communication

In our day-to-day interactions, exaggeration often serves as a social lubricant. We might say, “I’ve told you a million times,” to express frustration. Though clearly an exaggeration, it effectively communicates the emotion behind the statement. This form of communication can strengthen relationships by adding humor and clarity.

Common Mistakes in Memory Exaggeration

While exaggeration can enhance memory, it can also lead to inaccuracies if not managed well. Here are some common pitfalls and how to avoid them:

- Over-Exaggeration: Overdoing it can lead to completely distorted memories. It’s essential to keep a balance between enhancing key details and fabricating false ones.

- Avoidance Tip: Regularly revisit memories and compare them with factual records or other people’s recollections to maintain accuracy.

- Emotional Distortion: Strong emotions can exaggerate memories. Be aware that feelings of fear or excitement might amplify memories beyond reality.

- Strategy: Practice mindfulness and try to detach emotions from memories when recalling events to prevent distortion.

- Lack of Verification: Relying solely on exaggerated memories without cross-checking facts can lead to misinformation. Always verify critical information, especially in professional settings.

- Practical Approach: Keep notes or a diary to have a factual reference point that can be compared against your memories.

Exaggeration Across Cultures

Cultural differences can influence the degree and style of exaggeration. In some cultures, storytelling with embellishments is expected and appreciated, while in others, precision and accuracy are valued more highly.

Cultural Variations in Storytelling

In cultures with a strong oral tradition, such as those in many African and Indigenous communities, exaggeration is often a tool for teaching and preserving history. Stories passed down through generations are embellished to emphasize moral lessons or cultural values.

- Example: Folktales from West Africa often feature animals with human characteristics performing exaggerated feats to convey wisdom or cultural norms.

Future Research Directions

The study’s researchers are keen to explore how exaggeration affects different age groups, particularly older adults. As people age, memory capacity often changes. Understanding whether exaggeration diminishes with age could provide insights into memory-related challenges faced by seniors.

Potential Areas of Research

- Age-Related Changes: Investigating how exaggeration in memory changes with age could lead to improved techniques for memory retention in older adults.

- Hypothesis: Older adults might rely more on exaggeration to compensate for declining memory capacity.

- Impact of Technology: Examining how digital media and technology influence our tendency to exaggerate, especially with the rise of social media where embellishments are rampant.

- Research Question: Does the constant bombardment of exaggerated content on social media alter our brain’s natural exaggeration tendencies?

- Therapeutic Applications: Exploring exaggeration’s potential in therapeutic settings, such as using exaggerated narratives to help patients with trauma reframe their experiences.

- Application: Therapists could utilize storytelling with controlled exaggeration to help patients process and reinterpret traumatic memories.

Embracing the Benefits of Exaggeration

Embracing the concept of exaggeration in memory can enhance our cognitive abilities and storytelling skills. By understanding and utilizing this natural brain function, we can improve our memory, communicate more effectively, and enrich our lives with colorful, engaging experiences.

Personal Development

Using exaggeration strategically can also lead to personal growth. By practicing storytelling and memory techniques that employ exaggeration, individuals can improve public speaking skills, enhance creativity, and even boost confidence.

- Exercise: Try recounting a mundane day with exaggerated details to practice engaging storytelling.

As research continues, we can look forward to even more fascinating insights into how our brains work and how we can harness these quirks to our advantage. Embracing exaggeration not only enriches our narratives but also deepens our understanding of human cognition and communication.