HIV isn’t an abstract concept or a headline from decades ago. It’s a virus that still affects millions of people, yet we now have the tools to prevent transmission, detect infection earlier than ever, and help people live long, healthy lives. I’ve sat with patients navigating a new diagnosis, worked with parents worried about transmission in their families, and seen the relief on someone’s face when their viral load becomes undetectable. Consider this your clear, trustworthy guide: what HIV is, how it spreads, how to recognize the stages, and what modern care actually looks like.

What HIV Is and How It Works

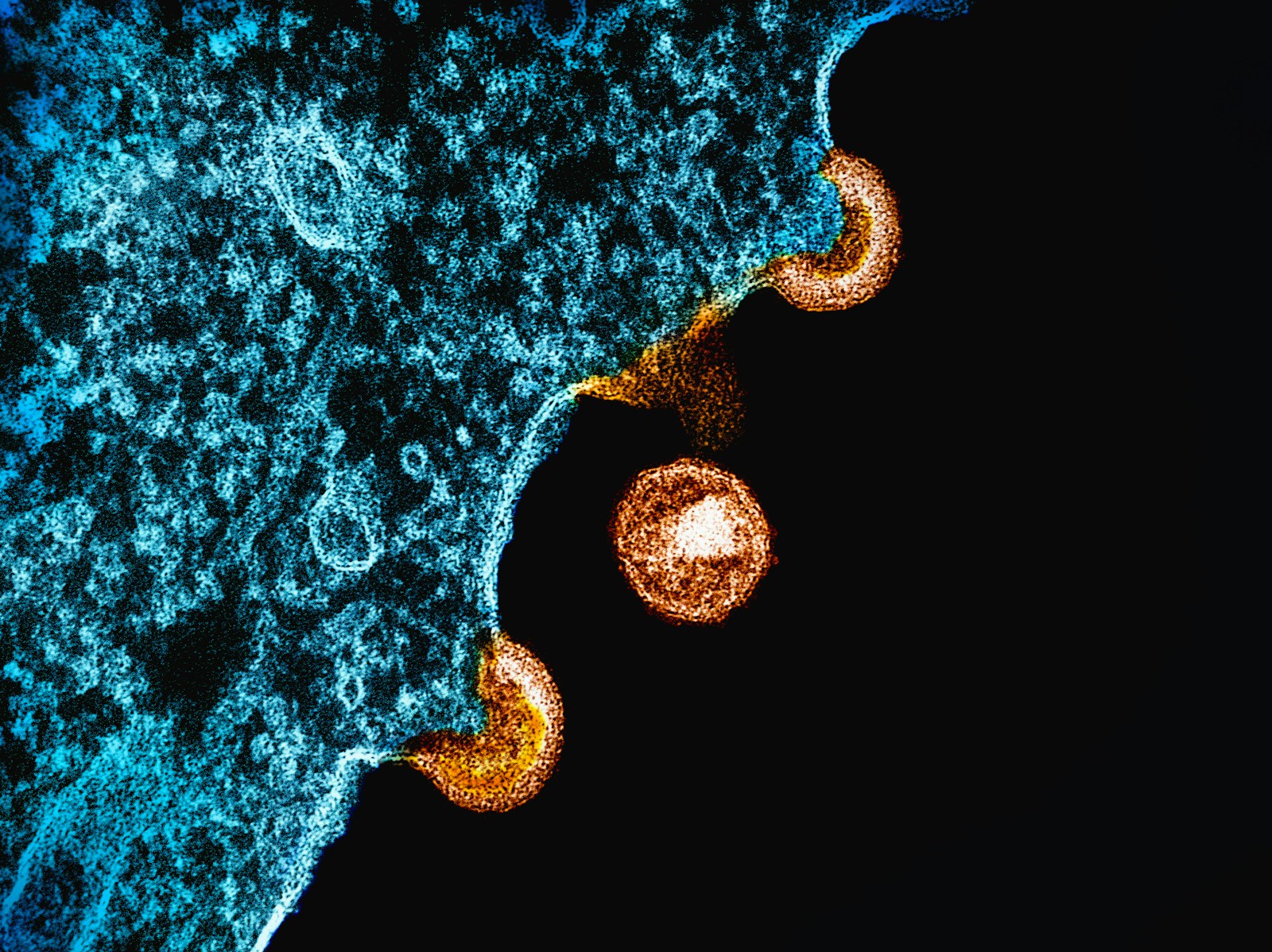

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) attacks the immune system, specifically the CD4 T cells that orchestrate immune responses. Left unchecked, HIV gradually reduces the number of these cells, weakening the body’s defenses and increasing the risk of infections and certain cancers. AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is the advanced stage of HIV, defined by a CD4 count below 200 cells/mm³ or the presence of specific opportunistic infections.

Key Points About the Virus

- Integration into DNA: HIV integrates into human DNA. That’s why treatment suppresses replication but doesn’t completely eliminate latent reservoirs.

- Clinically Silent Period: Without treatment, there’s often a long clinically silent period, even as the virus steadily damages the immune system.

- Immune Recovery with Treatment: With treatment, the immune system can recover and remain healthy for decades.

Global Context

- Approximately 39 million people are living with HIV worldwide.

- Around 1.3 million people acquire HIV each year.

- AIDS-related deaths have fallen dramatically since the height of the epidemic, thanks to broader access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), but hundreds of thousands still die annually—often due to late diagnosis or gaps in care.

How HIV Spreads (and How It Doesn’t)

HIV is transmitted via specific body fluids: blood, semen (including pre-seminal fluid), vaginal fluids, rectal fluids, and breast milk. For transmission to occur, these fluids need to come into contact with a mucous membrane, damaged tissue, or be directly injected into the bloodstream (such as via a needle).

Main Routes of Transmission

- Sexual Contact: Vaginal or anal sex with a person living with HIV who has a detectable viral load.

- Needle Sharing: Sharing needles or syringes for injecting drugs, hormones, or steroids.

- Mother-to-Child: During pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding, if the mother is not on effective treatment or not virally suppressed.

- Blood Transfusion or Organ Transplant: Extremely rare in countries that screen blood; risk remains where screening is inconsistent.

- Occupational Exposure: Needlestick injuries in healthcare settings (rare and preventable, with post-exposure protocols).

What Does Not Transmit HIV

- Hugging, shaking hands, casual contact

- Closed-mouth kissing (deep kissing carries an extremely low risk unless both partners have bleeding gums or open sores, and even then it’s highly unlikely)

- Sharing dishes, beverages, or toilets

- Saliva, sweat, and tears, unless visibly contaminated with blood

- Mosquitoes or other insects

The Role of Viral Load

- Viral Load: The amount of virus in the blood. Higher viral load means higher risk of transmission.

- U=U (Undetectable = Untransmittable): People with sustained undetectable viral load do not sexually transmit HIV. This is supported by large studies of thousands of condomless sexual acts with zero linked transmissions.

The Science of Risk: What Raises or Lowers the Chance of Transmission

Transmission isn’t random; it’s probabilistic and driven by measurable factors.

What Increases Risk

- High viral load

- Certain types of sex: Receptive anal sex carries the highest sexual transmission risk per act; receptive vaginal sex carries lower but still significant risk.

- Co-existing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that cause inflammation or lesions

- Genital ulcers or bleeding

- Sharing needles/syringes or other injection equipment

- Acute HIV infection (the first weeks after acquiring HIV), when viral load is typically very high

What Lowers Risk

- Antiretroviral therapy with sustained undetectable viral load (U=U)

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-negative people at ongoing risk

- Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after a potential exposure

- Condoms, when used consistently

- Harm reduction for people who inject drugs, such as access to sterile injecting equipment

- Voluntary medical male circumcision, which reduces men’s risk of acquiring HIV from female partners

Approximate Per-Act Risks Without Prevention Measures (Estimates Vary by Study)

- Receptive anal sex: about 1% to 2% per act

- Insertive anal sex: roughly 0.1% to 0.3% per act

- Receptive vaginal sex: around 0.05% to 0.1% per act

- Insertive vaginal sex: about 0.02% to 0.05% per act

- Oral sex: very low but not zero, especially if there are sores or bleeding gums

Condoms substantially reduce risk (roughly 80% or more with consistent use). Daily PrEP lowers sexual transmission risk by around 99% when taken as prescribed; for people who inject drugs, PrEP reduces risk significantly as well. PEP, if started promptly within 72 hours and taken for the full 28 days, can dramatically lower the chance of infection from a specific exposure.

Symptoms: What to Expect at Different Stages

HIV behaves differently over time. Some people have noticeable symptoms early on; others don’t notice anything until later.

Acute HIV (First Weeks After Exposure)

This phase often involves a transient illness that can be mistaken for the flu or mononucleosis:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Rash (often maculopapular, on trunk)

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Night sweats

- Mouth ulcers or headache

These symptoms typically appear 2 to 4 weeks after exposure and resolve within a few weeks. During this time, the viral load is high and the risk of transmission is greatest. Many people miss this phase because the symptoms are nonspecific.

Chronic/Latent Phase (Months to Years)

After acute infection, the immune system and the virus reach a kind of standoff. Symptoms may be minimal or absent while the virus continues to replicate. Without treatment, CD4 counts gradually drop.

- Persistent lymph node swelling

- Recurrent minor infections (e.g., thrush, shingles)

- Low-grade fevers, weight loss, or night sweats

Advanced HIV/AIDS

Severe immune suppression can lead to opportunistic infections and certain cancers:

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) causing shortness of breath and dry cough

- Toxoplasma encephalitis (neurologic symptoms)

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis (vision problems)

- Tuberculosis (TB) reactivation or new infection

- Candidiasis of the esophagus

- Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Wasting syndrome

With modern therapy, many people never reach this stage, especially if diagnosed early.

Getting Tested: What Each Test Means

Testing is the only way to know your status. I’ve seen people wait months because they “felt fine” or had a single negative test too soon after a possible exposure. Understanding timing helps you avoid false reassurance or unnecessary anxiety.

Common Test Types

- Antibody Tests (Rapid or Lab-Based): Detect the body’s antibodies to HIV. Window period typically around 23 to 90 days after exposure.

- 4th-Generation Antigen/Antibody Tests: Detect both antibodies and the p24 antigen. Window period often around 18 to 45 days.

- Nucleic Acid Test (NAT, HIV RNA): Detects the virus directly. Window period around 10 to 33 days and used when acute infection is suspected or for indeterminate results.

Window Periods Matter

A negative result before the end of the window period doesn’t completely rule out infection; a follow-up test is needed.

Interpreting Results

- Negative: No HIV detected. If within the window period, retest according to the type of test and timing of exposure.

- Positive (Reactive): Needs confirmatory testing (usually a supplemental antibody differentiation assay and/or NAT).

- Indeterminate or Inconclusive: Repeat testing is required; a NAT can clarify acute infection.

Home Tests

- Home-Based Oral Swab Antibody Tests: Offer convenience and privacy. They’re useful, but the window period is longer than a lab-based 4th-generation test. If there’s been a recent exposure, follow-up with lab testing is appropriate.

A Practical Testing Timeline Example After a Single Possible Exposure

- At 10 to 14 Days: NAT can detect most infections, but may not be widely available for screening.

- At 3 to 4 Weeks: 4th-generation lab test catches many infections.

- At 6 Weeks: 4th-generation testing detects the vast majority.

- At 3 Months: Antibody tests detect nearly all infections.

If You’ve Had a Possible Exposure

Time matters. If an exposure occurred within the last 72 hours—such as condom breakage with a partner of unknown status or a needlestick injury—post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) can substantially reduce the risk of acquiring HIV.

What a Typical PEP Process Looks Like

- Immediate Evaluation: A clinician assesses the exposure type and timing, and checks for other risks (e.g., hepatitis B, C).

- Baseline Testing: HIV testing before starting PEP, plus pregnancy testing for those who could be pregnant, and STI screening where relevant.

- Start PEP as Soon as Possible: Ideally within hours. A standard course is three antiretroviral drugs for 28 days.

- Follow-up Testing: Repeat HIV testing at 6 weeks and again at 3 months to confirm status.

- Transition Plan: If ongoing risk is present, a conversation about moving from PEP to PrEP is common.

If the 72-hour window has passed, PEP is generally not recommended. Focus shifts to appropriate testing and prevention going forward.

Treatment Today: Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

ART changed everything. Modern treatment suppresses the virus to undetectable levels, restores immune function, and prevents transmission. Most people start with once-daily regimens and see viral load drop substantially within weeks.

Goals of ART

- Suppress viral replication to undetectable levels

- Allow CD4 counts to recover or stabilize

- Prevent illness and extend life expectancy to near-normal ranges

- Eliminate sexual transmission when sustained undetectable (U=U)

When to Start

- As Soon as Possible After Diagnosis: Same-day or rapid-start ART is routine in many clinics. Starting quickly doesn’t mean rushing blindly; baseline labs and resistance testing are done, but treatment need not be delayed while awaiting every result, unless there’s a specific concern (e.g., suspected cryptococcal meningitis in advanced disease).

Classes of Antiretroviral Drugs (Simplified)

- NRTIs (Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors): Backbone drugs such as tenofovir (TDF, TAF), emtricitabine (FTC), lamivudine (3TC), abacavir (ABC)

- INSTIs (Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors): Dolutegravir (DTG), bictegravir (BIC), raltegravir (RAL), cabotegravir (CAB)

- NNRTIs (Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors): Rilpivirine (RPV), doravirine (DOR), efavirenz (EFV)

- PIs (Protease Inhibitors): Often boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat; darunavir is commonly used

Common First-Line Regimens

- Bictegravir/Tenofovir Alafenamide/Emtricitabine (BIC/TAF/FTC): Single-tablet, once daily

- Dolutegravir Plus Tenofovir (TAF or TDF) Plus FTC or 3TC

- Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (DTG/3TC): A two-drug option for eligible patients without hepatitis B coinfection and with viral load below certain thresholds

- For Specific Scenarios: Boosted protease inhibitor–based regimen such as darunavir/cobicistat plus two NRTIs may be used

Long-Acting Injectables

- Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine: As a long-acting injectable combination given every 1–2 months can maintain suppression in people who are already undetectable on oral therapy and meet certain criteria. It isn’t typically used to start therapy in people who are not yet suppressed.

Laboratory Monitoring

- Viral Load and CD4 Count at Baseline

- Viral Load: At about 4 weeks after starting or changing therapy, then every 3–6 months once stable

- CD4: Every 6–12 months once stable, or more frequently if low

- Metabolic Labs: Kidney, liver, lipids, glucose, especially with regimens that can affect these systems

Resistance Testing

- Genotype Test: Guides regimen selection if there’s concern for transmitted resistance or virologic failure.

- Resistance Development: Primarily when the virus replicates in the presence of suboptimal drug levels, which is why consistent dosing matters.

What Success Looks Like

- Viral Load: Becomes undetectable (below the assay’s limit, often <20–50 copies/mL) usually within 8 to 24 weeks, sometimes sooner.

- CD4 Counts: May rise steadily; the degree of recovery depends on how low they were at baseline and other factors like age and coinfections.

Side Effects and How They’re Managed

Modern ART is far better tolerated than older regimens. That said, side effects still come up, especially in the first few weeks.

Short-Term Effects That Often Improve Over Time

- Nausea, diarrhea, or stomach upset

- Headache

- Sleep changes or vivid dreams (more common with some agents like efavirenz, which is less commonly used today)

Potential Long-Term Considerations

- Kidney Function: More relevant with TDF; TAF has a more favorable renal profile

- Bone Mineral Density: TDF can reduce bone density modestly; this usually stabilizes and can be mitigated by switching when necessary

- Weight Gain: Seen in some individuals after starting ART, especially with integrase inhibitors and TAF; the clinical significance varies

- Lipids and Cardiovascular Risk: Some regimens affect cholesterol; regular monitoring helps tailor care

- Drug-Drug Interactions: Boosted PIs and some NNRTIs have more interactions; check other meds and supplements

When side effects persist or interfere with daily life, switching regimens is often effective. There are multiple equally potent options that allow personalization.

Living Undetectable

Reaching undetectable viral load can take a weight off your shoulders. I’ve watched patients’ confidence and relationships improve once suppression is steady and they understand U=U.

What Undetectable Means in Practice

- No Sexual Transmission: Large studies demonstrate zero linked transmissions from partners with sustained undetectable viral load.

- Better Health Outcomes: Fewer illnesses, stronger immune system, longer life expectancy comparable to HIV-negative peers when diagnosed and treated early.

- Flexibility in Life Planning: Pregnancy, career goals, travel, and sport are all possible with thoughtful care.

Staying undetectable involves consistent treatment, attending routine follow-ups, and addressing issues like side effects or life changes that could affect medication schedules. If a viral load “blip” occurs (a small, single rise in viral load) and quickly returns to undetectable, that’s generally not a cause for alarm; sustained increases are evaluated for adherence, interactions, or resistance.

Special Situations and Populations

Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- Effective ART during Pregnancy: Reduces the risk of transmission to less than 1% when viral suppression is maintained.

- Dolutegravir-Based Regimens: Widely used and considered safe throughout pregnancy based on growing data.

- Delivery Planning: Depends on viral load near term; vaginal delivery is often appropriate if undetectable.

- Infant Prophylaxis After Birth: Standard. Breastfeeding guidance varies by region and resources:

- In settings with safe alternatives, formula feeding is commonly recommended to eliminate postnatal transmission risk.

- Where breastfeeding is the norm and formula is unsafe or inaccessible, breastfeeding with maternal viral suppression and infant prophylaxis can be safer overall than formula feeding. Local guidelines and pediatric infectious disease input guide decisions.

Adolescents and Young Adults

- Transitional Care: Matters as teens move from pediatric to adult services.

- Confidentiality, Mental Health, and Support Systems: Crucial in adherence and outcomes.

Aging with HIV

- Longer Living with HIV: Means age-related conditions (heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, osteoporosis) are part of routine care.

- Drug Interactions Increase: As medication lists grow. A “medication reconciliation” at each visit helps catch conflicts.

Coinfections: Hepatitis and TB

- Hepatitis B: Tenofovir plus FTC or 3TC treats both HIV and HBV. Stopping these drugs without proper management can flare hepatitis B.

- Hepatitis C: Curable with direct-acting antivirals; timing with ART and drug interactions should be reviewed by a clinician familiar with both.

- Tuberculosis: Can occur at any CD4 count but is more common with advanced immunosuppression. Preventive therapy (e.g., isoniazid or rifapentine-based regimens) is used for latent infection. Active TB requires a specific multi-drug regimen and careful coordination with ART due to drug interactions.

Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis

- Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP): If CD4 <200 cells/mm³, prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is standard until CD4 recovers.

- Toxoplasma Gondii: If CD4 <100 and positive toxoplasma IgG, TMP-SMX also prevents toxoplasmosis.

- Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC): Routine prophylaxis is less common when ART is started