Leg-lengthening surgery has captured headlines for its ability to add inches to a person’s height, but the procedure isn’t new. Developed to treat serious medical problems like limb‑length discrepancies and skeletal deformities, limb‑lengthening surgery has helped countless patients walk more comfortably, avoid posture‑related pain and prevent joint problems. In recent years, however, the technique has been co‑opted by people without medical need who want to gain a few inches simply for personal satisfaction. That trend raises complex questions about ethics, risk and the blurred line between reconstructive and cosmetic surgery. To understand whether leg lengthening is worth it, it helps to know how the procedure works, who it was designed for and why experts stress caution.

Understanding Limb‑Lengthening Surgery

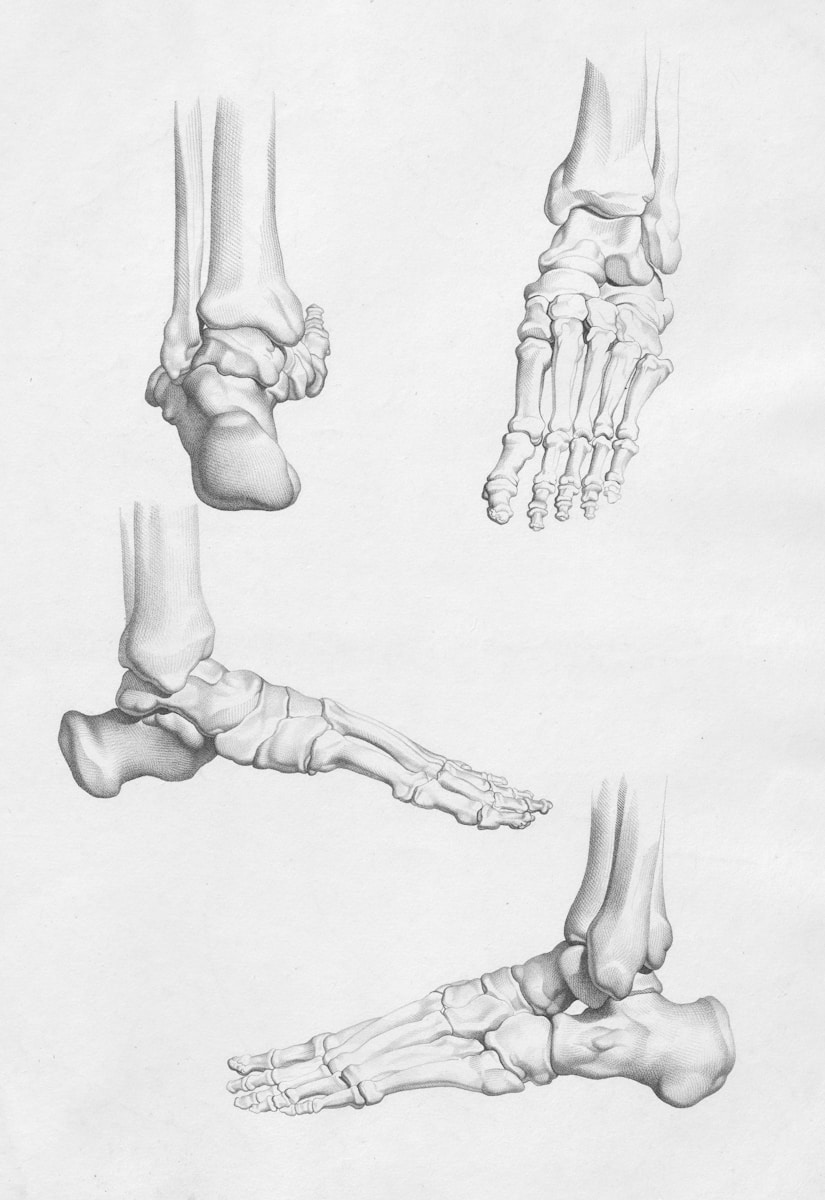

Limb‑lengthening surgery is a medical procedure that gradually makes a bone longer. The technique can be used on arms or legs and is typically performed by orthopedic surgeons trained in deformity correction. When a person has one leg that’s significantly shorter than the other, their pelvis tilts and their spine curves to compensate. Over time, they may develop back pain, hip and knee problems, or difficulties with balance and gait. Conditions that lead to limb‑length differences include skeletal dysplasia (a group of disorders that affect bone growth), congenital femoral deficiency, bone growth disorders, traumatic injuries that stop a limb from growing, or bone tumors removed during childhood. Historically, surgeons recommended limb‑lengthening only when the difference in limb length interfered with daily activities; discrepancies smaller than about two centimeters can often be managed with shoe lifts or prosthetic adjustments. Major centers like Boston Children’s Hospital emphasize that careful evaluation of limb stability, tissue health and the degree of length discrepancy guides the decision to lengthen a bone.

A Brief History: From Ilizarov to Modern Devices

Limb lengthening traces its roots to Gavriil Ilizarov, a Russian orthopedic surgeon who developed an external fixation frame in the 1950s. Ilizarov discovered that slow, controlled distraction (pulling apart) of a bone could stimulate the body to create new bone tissue in the gap. This Ilizarov technique revolutionized reconstructive orthopedics and was later refined by Italian and American surgeons. Today, limb‑lengthening devices fall into two categories: external fixators and internal lengthening rods. External fixators are metal frames that encircle the limb and connect to the bone via pins or wires. Patients or caregivers adjust the frame gradually to separate the bone ends. Internal rods such as the PRECICE nail are inserted inside the bone and lengthened by a magnetic controller placed on the skin; these devices reduce the risk of skin infection and are removed once healing is complete.

How the Procedure Works

Limb‑lengthening capitalizes on the body’s natural healing ability through a three‑stage process: surgery, distraction and consolidation.

Preoperative Planning

Before surgery, doctors take X‑rays to measure the bone and plan how much lengthening is needed. They assess the joints above and below the targeted bone to ensure they can withstand the mechanical forces of lengthening. In most cases, surgeons recommend lengthening only if the limb is stable, the surrounding tissues are healthy and the patient is willing to commit to months of therapy and follow‑】or cosmetic candidates, doctors also evaluate psychological readiness, as the procedure is physically demanding and may not satisfy underlying body‑image issues.

Stage One: Surgery

In the first stage, the surgeon makes an osteotomy — a controlled surgical cut through the bone. Great care is taken to preserve the bone’s blood supply and the surrounding soft tissue. Once the bone is cut, the surgeon attaches the lengthening device. If an external frame is used, pins or wires are inserted through the skin into the bone and secured to a circular or linear frame. If an internal rod is used, the surgeon inserts the motorized nail into the bone cavity and fixes it with screws. Patients typically stay in the hospital for a day or two after surgery to manage pain and begin learning how to care for the device-】.

Stage Two: Distraction (Lengthening)

After about a week of rest, the distraction phase begins. During this stage, the two ends of the bone are slowly pulled apart at a rate of roughly 1 millimeter per day. This tiny gap stimulates the formation of new bone tissue (called regenerate bone) in the space between the bone ends. With an external fixator, the patient or caregiver uses a small wrench to turn bolts on the frame several times each day. With an internal rod, a magnetic controller placed on the skin activates the motorized nail and lengthens it incrementally. Surgeons monitor progress closely through regular X‑rays. If new bone grows too slowly or quickly, or if soft tissues show signs of excessive tension, the surgeon adjusts the lengthening rate or pauses to allow the body to rest.

Stage Three: Consolidation (Healing)

Once the limb reaches its planned length, the consolidation phase begins. The distraction stops, but the device remains in place while the new bone hardens and matures. Healing generally takes twice as long as the lengthening itself, so a two‑month distraction period may require four months of consolidation. During this time, the nerves, muscles, tendons and ligaments adapt to the new length. Physical therapy is critical to maintain joint mobility and muscle strength; without diligent stretching and exercise, patients may develop contractures or joint stiffness.

How Long Does it Take?

The entire limb‑lengthening process can span six to nine months, sometimes longer. Bones are usually lengthened two inches (5 centimeters) per cycle, and surgeons rarely exceed 25 percent of a leg’s original length in one cycle. People seeking greater gains may undergo a second lengthening cycle after the bone has fully healed, but each cycle adds months of rehabilitation. This extended timeline is one reason surgeons caution against viewing limb lengthening as a quick fix for short stature.

Who Is Eligible for Leg‑Lengthening Surgery?

Surgeons weigh several factors when deciding whether a patient is a good candidate for limb lengthening:

- Limb stability: The joints above and below the bone must be healthy and able to tolerate the forces of lengthening. Unstable joints can dislocate as the bone is stretched.

- Tissue health: Scarred or damaged muscles and skin (from trauma or infection) may not stretch easily and could be injured during lengthening.

- Degree of discrepancy: Small differences (less than 2 centimeters) rarely require surgery; shoe lifts or orthotics can compensate. Larger discrepancies that interfere with walking, standing or limb alignment may justify surgery.

- Age and growth: Children and young adults are ideal candidates because their bones heal quickly and they have more growth potential. Adults can undergo lengthening, but recovery may take longer and complications may be more likely.

- Commitment: Limb lengthening demands daily adjustments, frequent clinic visits and months of physical therapy. Patients and families must be prepared for this intensive process.

Cosmetic stature lengthening uses the same techniques but on otherwise healthy bones. Candidates usually have fully grown skeletons and are often motivated by psychological distress about their height. Many centers require psychological screening to ensure that patients understand the risks and have realistic expectations. Some clinics cap the amount of length gained per surgery (often around 6–7 centimeters) to reduce complications.

Risks and Complications

Every surgeon interviewed for this article emphasized that complications are common in limb lengthening. According to Boston Children’s Hospital, potential problems include pin‑site infection, muscle contractions, joint dislocations, blood vessel and nerve injuries, delayed or accelerated bone formation, and bone non‑union (failure of the new bone to heal properly). Cleveland Clinic lists additional complications: stiff joints, muscle weakness, unequal bone growth, device malfunction, and in rare cases, failure of the lengthening to achieve the desired length.

Infection

External frames create pathways for bacteria to enter through the pins. Pin‑site infections can occur despite meticulous care. Symptoms include redness, warmth, pain and drainage around the pin sites. Treating these infections early with antibiotics is essential to prevent deeper bone infection (osteomyelitis). Internal rods avoid pin‑site infection but still carry a small risk of infection around the surgical incisions.

Soft Tissue Complications

As the bone lengthens, muscles, tendons and nerves stretch as well. Overstretching can cause muscle tightness, joint contractures or nerve palsy. For instance, patients may develop foot drop if the nerve controlling the ankle becomes compressed. Surgeons slow or pause the distraction when these problems arise and may prescribe braces or additional physical therapy. In severe cases, additional surgery is required to release tight tissues.

Bone Healing Problems

Occasionally, the regenerate bone fails to form (non‑union) or hardens too quickly (premature consolidation). Non‑union may require bone grafting or revision surgery, while premature consolidation forces the surgeon to re‑cut the bone and restart the lengthening. Conversely, if the distraction proceeds too fast, the newly formed bone can be weak and prone to fracture. Careful monitoring helps surgeons adjust the rate of lengthening to ensure healthy bone growth.

Pain and Psychological Stress

Patients often experience significant pain during the initial postoperative period. While the lengthening itself may not be acutely painful, muscles and nerves can feel sore or tight. Chronic discomfort, limited mobility and reliance on caregivers can be mentally taxing. Some individuals report feelings of isolation or regret during the long recovery. Cosmetic candidates may also struggle if the final height increase does not meet their expectations.

Cost and Accessibility

Limb lengthening is expensive. In the United States, a single cycle can cost $70,000 to $150,000, and insurance typically covers it only for medically necessary cases. Cosmetic stature surgery is usually paid out of pocket. Patients must also account for lost wages if they cannot work during rehabilitation and for the cost of physical therapy and follow‑up visits.

Alternatives

For those with limb‑length discrepancies, non‑surgical options include shoe lifts, orthotic devices, epiphysiodesis (a procedure that slows growth in the longer limb) or prosthetics. In some cases, amputation and a prosthetic limb provide a more functional and less risky solution. Dr. James Kasser of Boston Children’s Hospital notes that for certain patients, amputation results in fewer surgeries and greater mobility than limb lengthening. For adults unhappy with their height, psychotherapy to address body‑image concerns may be a safer starting point.

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Healing from limb lengthening is a marathon, not a sprint. Patients typically require six to nine months before they can return to full weight‑bearing and normal activities. Early recovery focuses on wound care, pain control and device management. As the distraction phase progresses, physical therapy becomes central. Therapists teach stretching and strengthening exercises to prevent joint stiffness and maintain muscle balance. Aquatic therapy may help patients move more comfortably while the limb is fragile. Most people need assistive devices like crutches, walkers or wheelchairs during the distraction and early consolidation phases because the lengthened bone can’t yet bear full weight. Once the new bone hardens, patients gradually transition to standing and walking without support.

Nutrition also matters: a diet rich in protein, calcium and vitamin D supports bone healing. Surgeons often recommend avoiding smoking and alcohol, both of which can impair bone growth. Regular follow‑up appointments allow the surgical team to adjust the lengthening rate, monitor bone formation and address any complications promptly.

Psychological and Social Considerations

Leg‑lengthening surgery can profoundly affect a person’s identity and self‑image. For children with limb differences, successful lengthening may increase independence and reduce stigma. For adults seeking stature surgery, motivations range from improving self‑confidence to meeting societal expectations about height. However, experts caution that an operation will not automatically improve one’s life. People may need counseling to address underlying insecurities and to adjust to the lengthy recovery. Relationships and work responsibilities can be strained when a patient requires months of limited mobility and assistance. Both patients and families should weigh the social costs alongside physical risks.

Ethical Debates Around Cosmetic Height Surgery

The growing popularity of limb lengthening for purely cosmetic reasons has sparked ethical debates. Opponents argue that it medicalizes normal variation in height, exposes healthy people to unnecessary risk and reinforces societal biases that equate tallness with worth. Proponents contend that autonomy should allow individuals to change their bodies as they see fit, provided they are fully informed about the risks. Surgeons who perform cosmetic stature procedures emphasize strict selection criteria, comprehensive psychological evaluation and realistic goal setting. Some professional organizations caution against performing the surgery solely for aesthetic reasons and stress the need to prioritize patient safety and well‑being.

Making an Informed Decision

If you are considering leg‑lengthening surgery, either for yourself or your child, consult an orthopedic specialist with experience in limb lengthening and deformity correction. Ask detailed questions about the expected length gain, duration of treatment, potential complications, cost and alternatives. Seek a second opinion to ensure that surgery is the best option. In medically necessary cases, limb‑lengthening surgery can improve quality of life and prevent future musculoskeletal problems. In cosmetic contexts, the trade‑off between a few extra inches and the months of pain, expense and risk may not be worthwhile.

Conclusion

Limb‑lengthening surgery is a powerful yet demanding procedure. Born out of the need to treat significant limb‑length discrepancies, it relies on careful surgery and the body’s ability to regenerate bone. Advances such as motorized internal rods have made the process more comfortable, but the fundamentals remain the same: gradual distraction, constant monitoring and months of rehabilitation. While the procedure offers transformative benefits to patients with substantial leg‑length differences, it carries substantial risks, including infection, nerve damage, muscle contracture, delayed or failed bone healing and psychological stress. For individuals considering the surgery to become taller, it’s important to recognize that the path is long, the outcome uncertain and the complications inevitable. Instead of being seen as a quick fix for self‑esteem, leg lengthening should be approached as a last resort for those with significant functional impairments or carefully justified psychological needs.