Among the many horrifying diseases known to humanity, few are as bizarre and tragic as Kuru. This fatal neurodegenerative disorder, once prevalent among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea, was spread through an unusual and morbid practice—ritualistic cannibalism. Unlike most infectious diseases, Kuru was neither bacterial nor viral in nature; instead, it belonged to a rare and mysterious class of disorders known as prion diseases. These diseases are caused by misfolded proteins that trigger a chain reaction, leading to severe and irreversible damage in the brain.

The discovery of Kuru not only exposed the devastating effects of prion diseases but also shed light on how these illnesses propagate in human populations. The disease was first documented in the mid-20th century when Western scientists observed clusters of affected individuals in isolated villages. Through extensive field research, medical professionals determined that Kuru was directly linked to the Fore people’s mortuary feasting customs, where consuming the tissues of deceased relatives was a means of expressing love and respect. However, this practice inadvertently facilitated the spread of Kuru, particularly among women and children who often consumed the most infectious parts—the brain and spinal cord.

Kuru’s devastating effects and mysterious nature made it a subject of intense scientific inquiry. Researchers studying the disease uncovered fundamental mechanisms of prion transmission, significantly advancing the medical understanding of related conditions such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and mad cow disease. This article delves into the origins, symptoms, transmission, and far-reaching scientific discoveries associated with Kuru, illustrating how one small and isolated epidemic ultimately transformed global knowledge of neurodegenerative disorders.

The Origins of Kuru

The Fore People and Ritualistic Cannibalism

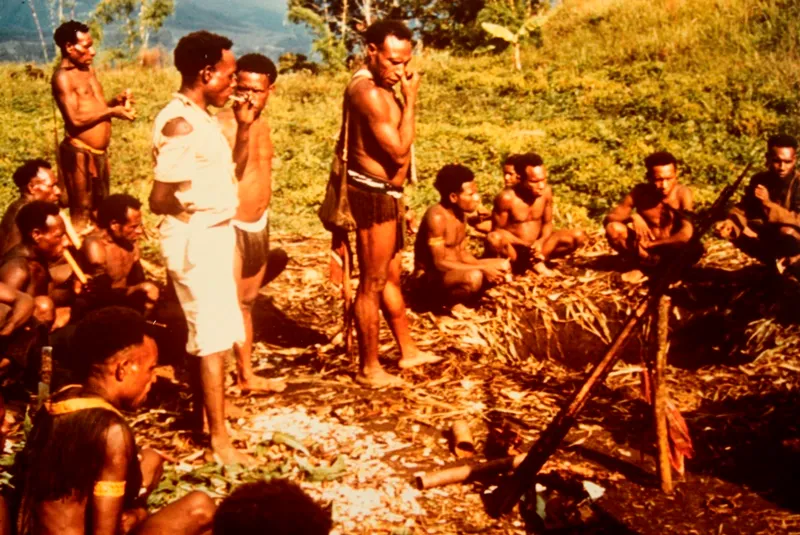

The Fore people, an indigenous group in Papua New Guinea, practiced a unique and deeply spiritual form of funeral rites that involved consuming the bodies of deceased relatives. This tradition was rooted in a belief system that emphasized the continuation of ancestral bonds beyond death. By consuming the flesh of their loved ones, the Fore believed they were ensuring that the spirits of the departed remained within the community, offering protection and guidance. However, this well-intended practice had tragic consequences, as it inadvertently spread Kuru. The disease disproportionately affected women and children, who were typically assigned the role of consuming the softer tissues, particularly the brain and spinal cord, which harbored the highest concentration of prions, the infectious agents responsible for Kuru. Over time, entire family lineages were decimated, leading to widespread fear and sorrow within the Fore society.

Discovery of the Disease

Kuru was first documented by Western scientists in the 1950s when Australian patrol officers and medical researchers noticed an unusual number of Fore people suffering from severe neurological symptoms. Reports emerged of villagers experiencing tremors, loss of coordination, and uncontrollable laughter, eventually deteriorating to a vegetative state before succumbing to the illness. Initially, the cause of the disease was unknown, and theories ranged from genetic disorders to toxic environmental exposure.

Dr. Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, a virologist and medical researcher, played a key role in identifying the disease and linking it to the cannibalistic practices of the Fore people. Through extensive fieldwork, he meticulously documented the symptoms and progression of Kuru, eventually confirming that it was transmitted through ingestion of infected human tissues. His groundbreaking research, along with experimental studies demonstrating the transmissibility of Kuru in primates, provided conclusive evidence that Kuru belonged to a new class of infectious agents: prions. This discovery laid the foundation for the study of other prion diseases and earned Gajdusek the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976. His work not only brought international attention to Kuru but also revolutionized the understanding of neurological diseases, opening new avenues in medical research.

Symptoms and Progression of Kuru

Early Symptoms

Kuru progresses through distinct stages, beginning with mild symptoms and gradually worsening. The initial signs include:

- Unsteady gait (loss of balance and coordination)

- Tremors (involuntary shaking)

- Muscle weakness

- Difficulty speaking

Advanced Stages

As the disease progresses, the symptoms become more severe, leading to:

- Uncontrollable laughter (often referred to as the “laughing sickness”)

- Inability to stand or walk

- Severe muscle atrophy

- Dementia and cognitive decline

- Involuntary muscle spasms

In its final stages, individuals with Kuru become completely incapacitated, unable to eat, move, or communicate. Death usually occurs within one to two years after symptoms first appear.

The Science Behind Kuru: Prion Diseases

What Are Prions?

Unlike viruses or bacteria, prions are misfolded proteins that cause normal proteins in the brain to become abnormal, leading to brain deterioration and fatal neurological disorders. They are resistant to heat, radiation, and disinfectants, making them especially difficult to eliminate.

Connection to Other Diseases

The study of Kuru has provided valuable insights into other prion diseases, including:

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD): A fatal brain disorder that occurs sporadically or through genetic inheritance.

- Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (Mad Cow Disease): A disease found in cattle that can be transmitted to humans through contaminated meat.

- Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI): A rare genetic disorder that causes progressive insomnia and neurodegeneration.

Decline and Eradication of Kuru

By the 1960s, the practice of cannibalism among the Fore people had largely ceased due to government intervention, health education, and the increasing awareness of the link between their mortuary feasting rituals and the spread of Kuru. Anthropologists, medical researchers, and local authorities worked together to encourage alternative funeral practices, leading to a gradual but significant decline in new cases of the disease. As a result, the number of Kuru cases dramatically dropped over the following decades.

However, because prion diseases have long incubation periods (sometimes spanning decades), isolated cases of Kuru continued to emerge well into the 2000s. Some individuals who had been exposed to infected tissue in their youth only developed symptoms much later in life, demonstrating the resilience and unpredictability of prion diseases. The persistence of these cases underscored the complexity of prion-related disorders and reinforced the need for ongoing research into their mechanisms and potential treatments.

Legacy of Kuru

The study of Kuru has had profound implications for modern medicine. It has helped scientists better understand neurodegenerative diseases, protein misfolding disorders, and the resilience of prions. Researchers studying Kuru played a crucial role in uncovering how prion diseases operate, leading to advancements in the understanding of conditions such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (Mad Cow Disease), and Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI). Additionally, insights from Kuru research have influenced studies on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, both of which share certain pathological characteristics with prion disorders.

Further, Kuru’s impact on medical science extended to biosecurity measures and food safety regulations. Lessons learned from the disease contributed to strict controls on the handling and processing of animal byproducts to prevent the spread of prion-related conditions in both humans and livestock. Understanding how Kuru spread within a small, isolated community also provided valuable insights into the epidemiology of infectious neurological diseases, which has been useful in managing other public health crises.

Conclusion

Kuru remains one of the most unique and tragic medical mysteries of the 20th century. What was once a deadly epidemic among the Fore people ultimately provided crucial knowledge that has shaped modern neuroscience and prion disease research. While Kuru has been eradicated as a public health threat, its legacy lives on in the fight against similar neurological disorders that continue to challenge the medical world today. The disease not only shed light on the devastating effects of prion infections but also highlighted the importance of cultural practices in disease transmission, demonstrating how deeply intertwined medical science and anthropology can be. Continued research into prions and neurodegeneration owes much to the pioneering efforts of those who studied Kuru, ensuring that its impact extends far beyond the communities it once afflicted.