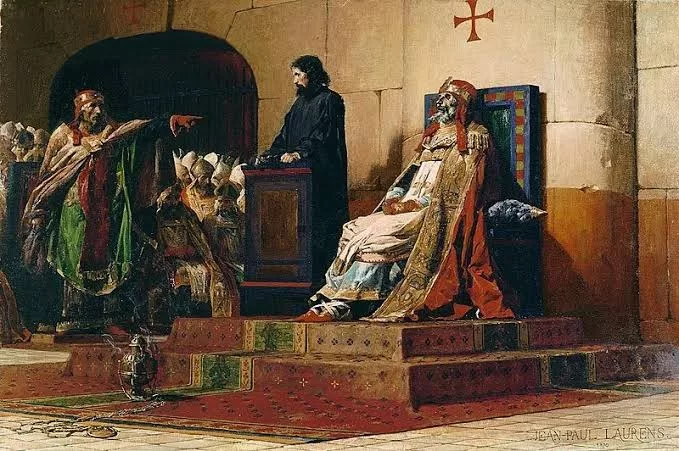

History is filled with strange episodes, but few are as grotesque and bewildering as the Cadaver Synod — a real ecclesiastical trial in which a long-dead pope was exhumed, dressed in papal robes, propped up on a throne, and put on trial by his successor.

It sounds like something out of a dark political satire or a medieval horror novel. But it really happened. In January of 897, in the city of Rome, Pope Stephen VI ordered the corpse of Pope Formosus to be dug up and brought to court. What followed was an event so absurd and so disturbing that it has continued to puzzle and fascinate historians for over 1,000 years.

The Cadaver Synod, also known as the Synodus Horrenda, is a grotesque symbol of just how toxic and cutthroat the politics of the early medieval papacy had become. It’s a story of revenge, power struggles, political factions, and religious hypocrisy—and it remains one of the darkest stains on the history of the Catholic Church.

Who Was Pope Formosus?

A Career Marked by Controversy and Exile

Formosus, born around 816 AD, had a long and eventful clerical career. Before becoming pope, he served as the Bishop of Porto, a prestigious position near Rome, and was sent on diplomatic missions to Bulgaria and France. He was widely respected for his intellect and political skills.

But Formosus also made enemies. In the turbulent politics of the 9th-century papacy, allegiances shifted rapidly, and he found himself on the wrong side of powerful factions. At one point, he was excommunicated by Pope John VIII, accused of plotting to seize the papacy for himself.

Though eventually restored, his political reputation remained checkered. When Formosus was finally elected pope in 891, the Church was already in chaos. He inherited a divided Rome and a fractious relationship with the powerful Carolingian and Spoleto dynasties that vied for influence over the papacy.

His “Crime”? Choosing the Wrong Emperor

The biggest controversy of Formosus’s papacy was his decision to invite Arnulf of Carinthia, a Germanic king, to invade Italy and depose Emperor Lambert of Spoleto, whom Formosus viewed as a threat to Church independence.

Arnulf did invade, and Formosus crowned him Holy Roman Emperor. But the victory was short-lived. Arnulf suffered a stroke shortly after and was forced to retreat. Formosus died in 896, just months later, leaving behind an unfinished power struggle — and a city seething with resentment.

Enter Pope Stephen VI: A Man on a Mission

The Puppet of the Spoletans

Stephen VI became pope in 896, backed by the Spoletan faction that Formosus had betrayed. These were dangerous men—nobles and warlords who used the papacy as a tool for regional control and dynastic power.

Stephen was likely pressured—or perhaps eager—to avenge the honor of Lambert of Spoleto and discredit Formosus once and for all. But instead of just denouncing his predecessor, Stephen took a more theatrical and sinister route.

He ordered Formosus’s corpse to be exhumed from its tomb in St. Peter’s Basilica, nine months after death.

Preparing a Corpse for Court

The decaying body was clothed in papal vestments and seated on a throne inside the Lateran Basilica. A deacon was appointed to speak on Formosus’s behalf, essentially voicing his defense. In one of the most disturbing events in papal history, a council of bishops and clergy gathered to try a dead man for “crimes against the Church.”

The charges included:

- Usurping the papacy

- Violating canon law by leaving his diocese to become pope

- Crowning an illegitimate emperor (Arnulf)

The Trial: A Grotesque Theater of Power

A Farce of Justice

The synod quickly descended into morbid spectacle. Stephen VI raged against the corpse, accusing Formosus of corruption, betrayal, and illegitimacy. The deacon, speaking on behalf of a decomposing body, tried in vain to refute the claims.

Eyewitness accounts describe Stephen becoming increasingly manic, shouting insults at the corpse, flinging its hand from the armrest, and physically shaking the body mid-rant. The clergy sat in stunned silence. What was happening wasn’t just unprecedented—it was unthinkable.

The Verdict

Unsurprisingly, the corpse of Formosus was found guilty. His papacy was declared invalid. All his acts as pope — including ordinations of bishops and clergy — were retroactively nullified. His body was stripped of its papal garments, three fingers of his right hand were cut off (those used in blessings), and he was buried in a pauper’s grave.

But it didn’t end there.

Shortly after, the body was dug up again, dragged through the streets of Rome, and thrown into the Tiber River.

Public Backlash and Retribution

Rome Turns on the Pope

The grotesque nature of the Cadaver Synod shocked even 9th-century Romans, who were used to political violence and papal intrigue. Many viewed the trial as a blasphemous act, a macabre and vindictive abuse of religious power.

Public opinion quickly turned against Stephen VI. Riots broke out. Within months, he was imprisoned, and later strangled to death in his cell.

The episode caused a ripple of outrage and confusion across Christendom. The very idea of posthumously trying a pope seemed both heretical and insane.

The Papacy Tries to Clean Up

Later popes tried to erase the embarrassment. Pope Theodore II (who reigned for just 20 days) ordered Formosus’s body to be recovered from the river and reburied in St. Peter’s with honors. Pope John IX convened a synod in 898 to annul the Cadaver Synod’s decisions, declare the trial invalid, and forbid any future trials of the dead.

But the damage had been done. The Cadaver Synod became a symbol of ecclesiastical madness, and Formosus’s legacy was permanently complicated.

Why It Happened: The Deep Politics Behind the Madness

More Than Personal Hatred

It’s tempting to write off the Cadaver Synod as the ravings of a mad pope. But the event reflected deep political fault lines in Europe. The papacy was not a neutral spiritual office — it was a powerful political prize, fought over by kings, nobles, and rival factions.

By trying Formosus posthumously, Stephen VI wasn’t just desecrating a corpse — he was attempting to erase a political rival’s legacy and reassert his faction’s control over Church law and imperial authority.

The question of who had the right to crown emperors, to appoint bishops, and to wield papal legitimacy was far from settled.

A Church in Crisis

The late 9th century was a low point for the papacy. Known as the beginning of the “Saeculum Obscurum” or “Dark Age of the Papacy,” this period saw the Roman Church become corrupt, violent, and dominated by secular forces.

Popes were regularly murdered, imprisoned, or bought and sold like political tokens. The Cadaver Synod was simply the most vivid symptom of a system in collapse.

Conclusion: A Trial That Stains the Pages of History

The Cadaver Synod remains one of the most macabre and baffling events in Church history — a moment when politics, religion, and madness collided in a public spectacle of decay, both moral and literal.

It reminds us that history is not always noble, and that the institutions we assume to be sacred can become twisted in the hands of those driven by fear, vengeance, and ambition.

Yet in its absurdity, the Cadaver Synod also serves as a warning. That power unchecked becomes grotesque, that justice without principle becomes theater, and that the line between piety and cruelty is often thinner than we imagine.

Formosus may have lost the trial. But in the end, it was Stephen VI who paid the price — not just with his papacy, but with his life.

Over a millennium later, we’re still talking about it. That, perhaps, is the final irony: the emperor who crowned the wrong king, the pope who was dragged back from the dead, and the Church that stood, even briefly, as a courtroom for a rotting corpse.

History, it turns out, has a strange sense of drama.