Herpes is one of those diagnoses that sounds scarier than it needs to be. It’s common, deeply misunderstood, and wrapped in more myths than almost any other infection. Over the years working with patients and writing about sexual health, I’ve seen the same questions come up again and again: How did I get this? What does it mean for my life and relationships? Can I treat it? This guide brings together what actually matters—what causes herpes, how it shows up, ways it spreads, how clinicians diagnose and manage it, and what living with it looks like in the real world.

Quick Orientation: What “Herpes” Actually Means

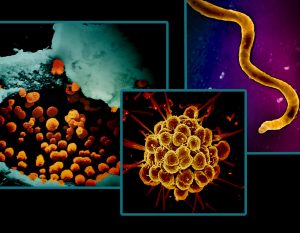

“Herpes” usually refers to infections caused by herpes simplex viruses: HSV‑1 and HSV‑2. They’re closely related, lifelong viruses that infect nerve cells and can cause recurring sores or symptoms on the skin and mucous membranes.

- HSV‑1 is traditionally associated with oral infections (cold sores), but it’s now a leading cause of genital herpes in many countries due to oral-genital contact.

- HSV‑2 is classically the genital strain and tends to recur more often in the genital area than HSV‑1 does.

Resetting the Conversation

- Herpes is extraordinarily common. WHO estimates suggest roughly two-thirds of people under 50 carry HSV‑1 globally, and about 13% of people aged 15–49 carry HSV‑2. Most people don’t know they have it.

- Many infections are silent. People can shed virus without visible sores, which is why it spreads easily.

- There’s no cure, but there’s excellent control. Modern antivirals reduce symptoms, shedding, and transmission risk—substantially.

- It’s manageable in relationships. With honest communication and modern management, couples navigate herpes successfully every day.

The Two Viruses, and How They Behave

HSV‑1 vs. HSV‑2 in Plain Language

- HSV‑1 (often oral, increasingly genital):

- Commonly caused by childhood nonsexual exposure (kisses from relatives, shared utensils, etc.), though oral sex now makes HSV‑1 a major cause of genital herpes in many regions.

- Genital HSV‑1 tends to recur less frequently than genital HSV‑2 and sheds less virus between episodes.

- HSV‑2 (primarily genital):

- Transmitted through sexual contact—vaginal, anal, and sometimes oral.

- More frequent recurrences and higher asymptomatic shedding rates in the genital area.

Both viruses establish latency in nerve ganglia (trigeminal for oral, sacral for genital) and can reactivate, especially when the immune system is taxed by illness, stress, fatigue, menstrual cycles, UV exposure (for oral HSV‑1), or skin irritation.

The Science in a Nutshell

After exposure, the virus enters skin or mucous membranes, replicates locally, travels up the nerve to a nearby ganglion, and settles in for the long haul. Future reactivations send virus back down to the skin, with or without noticeable sores. That’s why outbreaks recur in a similar area and why you can shed virus even when skin looks normal.

How Herpes Spreads—and How It Doesn’t

Routes of Transmission

- Skin-to-skin and mucosa-to-mucosa contact during sexual activity are the biggest drivers.

- Oral sex spreads HSV‑1 to the genitals and occasionally HSV‑2 to the mouth.

- Kissing transmits oral HSV‑1, especially during an active cold sore.

- Autoinoculation (spreading to another part of your own body) is most likely during a first episode when the immune response isn’t mature, then becomes uncommon.

- Transmission can occur without visible sores—this is asymptomatic shedding.

What Doesn’t Spread Herpes

- Toilet seats, swimming pools, shared towels after they’re dry, or casual social contact.

- Dishes and utensils are less of a concern outside of active cold sore episodes; HSV doesn’t survive long on dry surfaces.

Realistic Risk Perspectives

- Most HSV‑2 spread happens from people who don’t know they’re infected or are asymptomatic at the time.

- Using condoms or dental dams and avoiding sex during symptoms lowers risk, but not to zero, because herpes can shed from skin not covered by barriers.

- Suppressive antiviral therapy meaningfully lowers shedding and transmission.

In clinical research with discordant heterosexual couples (one partner has HSV‑2, the other doesn’t), daily valacyclovir reduced the risk of transmission by about 48% and cut symptomatic transmission even more. Consistent condom use offers additional protection. Different studies report varying numbers, but the combined effect of suppressive therapy plus barrier protection substantially lowers risk compared with doing nothing.

Symptoms: What People Actually Experience

First Episodes (The “Primary Outbreak”)

The first clinically noticeable episode often arrives 2–12 days after exposure, though it can appear later. Not everyone gets a “classic” first outbreak, but when it does appear, it can be more intense than recurrences:

- Painful grouped blisters that break into shallow ulcers

- Tender lymph nodes in the groin (genital) or under the jaw (oral)

- Fever, fatigue, headache, body aches—more common in primary HSV‑2 genital infections

- Burning, itching, tingling (prodrome) before lesions

- Painful urination if urine hits ulcers

- In people with vulvas, internal lesions can make it feel like a UTI

The first episode usually lasts 2–3 weeks without treatment. With antivirals, it shortens. Many people never get such a dramatic first outbreak; their “first sign” may be mild irritation, a fissure that’s mistaken for dry skin, or a single sore that looks like a shaving cut.

Recurrences

Reactivations tend to be milder and shorter:

- The prodrome (tingling, itch, nerve-like pain) is a clue.

- Fewer sores, less systemic illness.

- Oral HSV‑1 outbreaks often line the lip border; genital HSV‑2 recurrences cluster in the same general territory each time.

On average, genital HSV‑2 can recur several times a year early on (commonly 4–6 outbreaks in the first year), then it settles down for many. Genital HSV‑1 recurs less often—some people barely see it again after the initial episode. Oral HSV‑1 varies; some people have a cold sore once every year or two, others hardly ever.

Asymptomatic Shedding

A critical and underappreciated piece: no lesions doesn’t mean no virus. Genital HSV‑2 can shed on about 10–20% of days in the first year and decreases over time but never goes away. Genital HSV‑1 typically sheds less often. Suppressive antivirals and barrier methods cut this risk.

Locations Beyond the Mouth and Genitals

- Herpetic Whitlow: painful HSV infection of a finger, often from oral-genital contact or touching sores with broken skin.

- Ocular HSV (Herpes Keratitis): infection of the eye. This is an emergency because it can scar the cornea and affect vision. Red, painful eye, light sensitivity—needs urgent ophthalmology care.

- Eczema Herpeticum: widespread HSV on eczematous skin, especially in people with atopic dermatitis. Looks dramatic; requires prompt medical attention.

- HSV Encephalitis: rare but severe brain infection, usually HSV‑1, with fever, confusion, seizures. This is an ICU-level emergency.

Diagnosis: Getting a Clear Answer

The Gold Standard in Active Lesions

- PCR/NAAT swab from a sore is the most accurate test when lesions are present. It tells you if HSV is there and which type (1 or 2).

- Viral culture is older and less sensitive, especially as sores are healing.

Timing matters: the fresher the blister or ulcer, the higher the chance of a positive result. Once a lesion completely heals, swabbing usually isn’t helpful.

Blood Tests: Helpful but Nuanced

- Type-specific IgG blood tests (glycoprotein G-based) can identify prior exposure to HSV‑1 or HSV‑2. They don’t tell you where the infection is located, only that your immune system has seen that type.

- Results can be tricky. Low index values can be false positives, especially for HSV‑2. Confirmatory testing (e.g., Western blot, where available) clarifies ambiguous results.

- Timing matters here too: IgG may take 2–12 weeks (sometimes up to 16) to turn positive after a new infection.

- IgM tests are not recommended; they’re nonspecific and can mislead.

Differential Diagnosis: Lookalikes

- Syphilis (painless chancre), chancroid (painful ulcers), aphthous ulcers (canker sores, which are not viral), traumatic fissures, shingles (dermatomal stripe of blisters), hand-foot-mouth disease (usually kids, Coxsackie virus), and even yeast or contact dermatitis can be confused with herpes in early stages.

In practice, I’ve seen many patients assume they have recurrent yeast infections when recurrent HSV is the real culprit—particularly when “yeast treatments” don’t help and there’s a tingling prodrome or tiny clustered sores. Swabbing during symptoms resolves the uncertainty.

How Clinicians Think About Risk and Transmission

Here’s the practical framework used in clinic to discuss risk with patients and couples:

- Most partners in long-term relationships eventually align their HSV status; many already do and just don’t realize it.

- Type matters. Genital HSV‑2 tends to shed and recur more than genital HSV‑1, so prevention strategies are often tailored more aggressively when HSV‑2 is involved.

- Daily suppressive antivirals reduce recurrences by roughly 70–80% and cut viral shedding substantially.

- In discordant couples, combining suppressive therapy and barrier protection meaningfully reduces transmission risk.

- Avoiding sexual activity during symptoms and prodrome remains a cornerstone of risk reduction, because that’s when shedding is highest.

- Oral-genital transmission (HSV‑1 to genitals) remains under-discussed. Cold sores can transmit even when they’re small or just tingling.

Treatment: What’s Available and How It Works

Antivirals: The Backbone of Management

Three oral medications dominate care:

- Acyclovir

- Valacyclovir (a prodrug of acyclovir with better absorption and convenient dosing)

- Famciclovir

They’re nucleoside analogues that target viral DNA replication. They don’t cure herpes, but they shut down replication during outbreaks and reduce the likelihood and intensity of recurrences. They can be used two ways:

- Episodic therapy: taken at the earliest sign of an outbreak (prodrome or first blister) to shorten and soften it.

- Suppressive therapy: taken daily to reduce the frequency of outbreaks and the odds of passing the virus to a partner.

Side effects are usually mild: headache, nausea, fatigue. At higher doses or in people with kidney disease, dose adjustments are considered. Decades of data support their safety, including during pregnancy.

Topicals and Over-the-Counter Products

- Topical acyclovir or penciclovir has modest benefits for oral HSV if started early; they’re less useful for genital HSV compared with oral therapy.

- Many OTC “cold sore” creams mainly numb or moisturize; they can ease discomfort but don’t change the virus’s course much.

- Topical steroids on active herpes lesions can make things worse by suppressing local immune response—except in certain doctor-guided cases like ocular HSV under ophthalmologic supervision.

Pain and Symptom Control

Discomfort can be a big part of the first episode. Clinicians often address pain with general pain relievers and local anesthetics when appropriate. If urination is painful due to external lesions, temporary strategies that minimize stinging are commonly discussed in clinics. Severe primary episodes sometimes need short-term stronger pain control.

Special Scenarios

- Pregnancy:

- Acyclovir and valacyclovir are widely used in pregnancy.

- If a birthing parent has a history of genital HSV, many obstetricians recommend suppressive therapy starting at 36 weeks to lower the chance of an outbreak during labor.

- If lesions are present or there are prodromal symptoms at delivery, a cesarean section is usually recommended to reduce the risk of neonatal herpes.

- New maternal infections late in pregnancy carry higher risk because antibodies haven’t yet developed.

- Neonatal Herpes:

- Rare but serious. It can involve the skin, eyes, mouth; or disseminate to organs; or affect the central nervous system.

- Requires immediate hospitalization and IV antivirals.

- Immunocompromised Patients:

- Outbreaks can be more severe, prolonged, and widespread.

- Suppressive therapy is used more readily, and doses may be adjusted.

- Herpes and HIV:

- Each can influence the other. HSV‑2 can increase HIV acquisition and transmission risk because of mucosal inflammation and microscopic breaks.

- In people living with HIV, controlling HSV reduces lesions and improves comfort; antiretroviral therapy for HIV also helps tame HSV.

- Ocular HSV:

- Requires prompt eye-care evaluation. Steroid eye drops are dangerous if misused in active epithelial disease; management is highly specialized.

Living with Herpes: Mindset and Practical Realities

Herpes is a medical condition, but the emotional and social side often overshadows the biology. I’ve sat with patients who were convinced their dating life was over, or that they “deserved” this diagnosis because of a single choice. Those beliefs crumble quickly once they learn how common herpes is and how well it can be managed.

Real-World Experience

- Most partners respond with empathy once they understand the facts.

- Disclosure conversations feel scary but often build trust.

- Counseling, peer support, or even a single conversation with a clinician who handles herpes routinely can be transformative.

- People resume happy, fulfilling sexual lives—often within weeks of their diagnosis.

Stigma thrives in silence and misinformation. Clarity, not catastrophizing, is what changes the experience.

Common Myths That Keep People Stuck

- “Only promiscuous people get herpes.” Reality: HSV‑1 and HSV‑2 are so common that a single exposure can transmit them. Many people acquire HSV‑1 in childhood, well before sexual activity.

- “If I don’t have sores, I can’t spread it.” Asymptomatic shedding is real. Risk is lower, but not zero.

- “Condoms eliminate risk.” They reduce risk; they don’t remove it. Herpes can shed from skin not covered by the condom.

- “HSV‑1 isn’t a big deal.” Oral HSV‑1 is common, but genital HSV‑1 can still be painful and transmissible. It typically recurs less than HSV‑2 in the genital area but deserves the same respect.

- “I’ll never have a normal sex life.” With suppressive therapy, barrier protection, and honest communication, most couples navigate herpes effectively.

- “I can tell by looking who has it.” Many infections are silent. Visual diagnosis without testing is unreliable.

The Clinical Visit: What the Process Looks Like

When someone comes in with a suspected outbreak, here’s how it usually unfolds:

- History and Context

- When did symptoms start? Any prodrome?

- Sex history and partner status, including oral sex.

- Prior similar episodes, STIs, or testing results.

- Pregnancy status and immune health.

- Physical Exam

- Visual inspection of lesions: number, location, stage (blister, ulcer, crust).

- Lymph node assessment and any signs of systemic illness.

- Swab Testing if Lesions Are Present

- PCR swab from a fresh lesion is collected.

- Type-specific results often return within a few days.

- Additional Labs (selected based on the situation)

- Type-specific HSV‑1/HSV‑2 IgG if there are no lesions to swab or to clarify baseline status.

- STI screening panel if indicated.

- Treatment Discussion

- Whether to start antivirals immediately (often yes for a first episode).

- Episodic versus suppressive therapy considerations for the future.

- Symptom relief strategies and safety considerations.

- Follow-Up Plan

- Reviewing results.

- Adjusting therapy.

- Discussing partner communication and pregnancy plans if relevant.

This structure helps patients walk away with clarity rather than worry.

How Clinicians Decide on Suppressive Therapy

The decision revolves around three pillars:

- Symptom Burden

- Frequent or severe recurrences.

- Significant prodromal pain or nerve irritation.

- Transmission Concerns

- A partner who is HSV‑negative or whose status is unknown.

- High anxiety around giving herpes to someone else.

- Life Context

- Professional requirements (e.g., people whose work is hindered by oral sores).

- Travel, stress, and other predictable triggers.

When those factors converge, daily suppressive therapy is often a strong fit. It reduces recurrences and makes many people feel more in control of their lives.

Prevention Explained Without Scare Tactics

No single strategy does everything, and that’s okay. Prevention is layered:

- Timing: outbreaks and prodrome are high-risk windows. Avoiding sexual contact then reduces spread.

- Antivirals: suppressive therapy lowers shedding in the background.

- Barriers: condoms and dental dams reduce contact with infectious skin and fluids.

- Communication: partners decide together which risks they’re comfortable with, especially in long-term relationships.

One place I see people get tripped up is oral sex. Cold sores may be small or just starting, and people underestimate their contagiousness. That’s a common way genital HSV‑1 is transmitted.

Statistics You Can Use to Calibrate Expectations

- HSV‑1:

- Around two-thirds of the global population under 50 has HSV‑1 antibodies (estimates vary by region).

- Oral HSV‑1 often starts in childhood; in some high-income countries, fewer children acquire it early, shifting more infections into adolescence and adulthood via sexual contact.

- HSV‑2:

- Roughly 13% of people aged 15–49 globally carry HSV‑2.

- Many don’t know they have it; about 80% of HSV‑2 infections are unrecognized at the time of diagnosis in some studies.

- Transmission Reduction:

- Daily valacyclovir in HSV‑2 discordant couples has been shown to cut transmission risk by almost half. Barrier use adds additional protection.

Numbers vary between populations, and