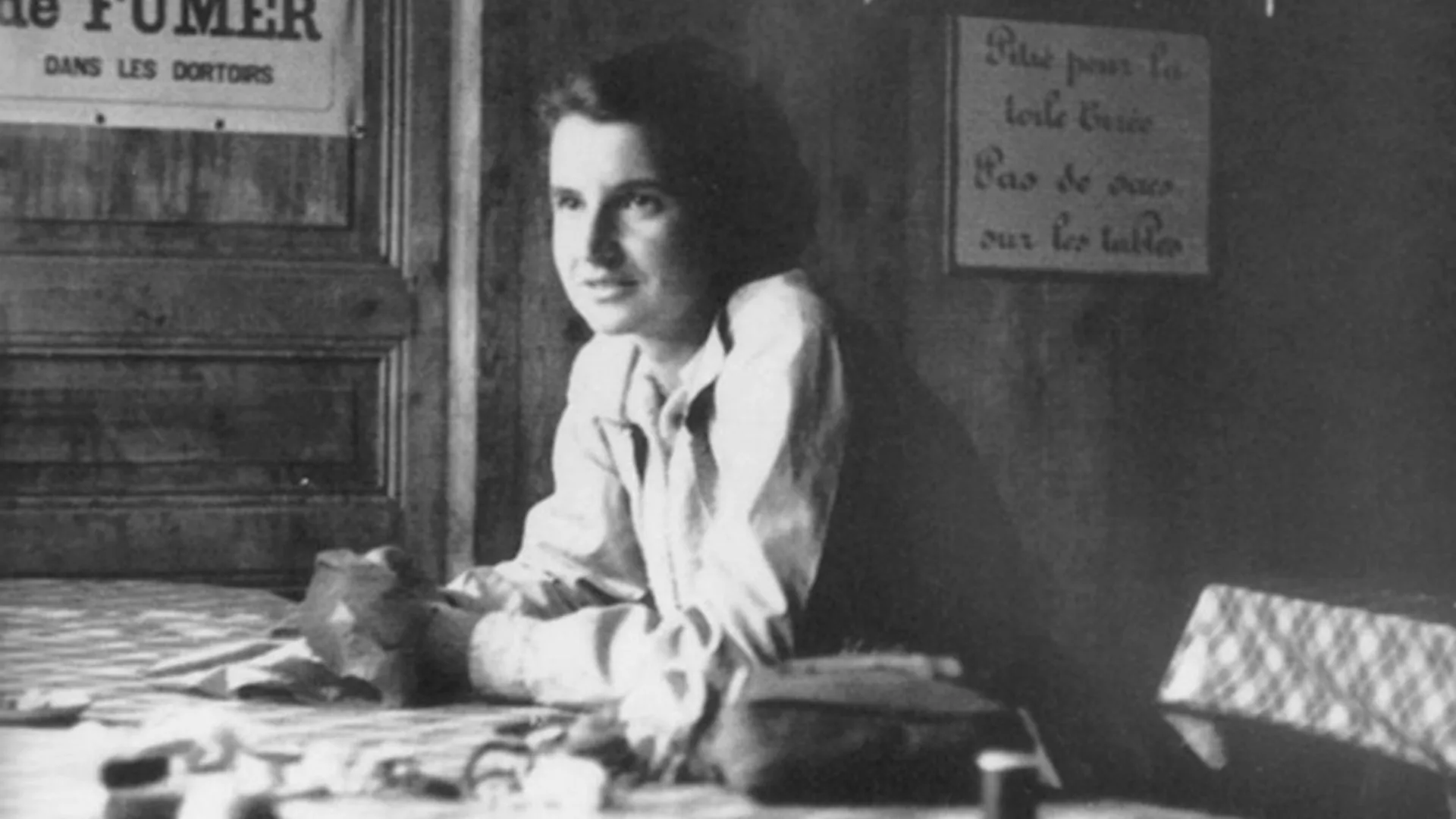

Rosalind Franklin was a pioneering scientist whose contributions to the discovery of DNA’s double helix structure were instrumental yet largely overlooked during her lifetime. A brilliant crystallographer and chemist, Franklin’s meticulous research and groundbreaking X-ray diffraction images provided the crucial evidence that allowed James Watson and Francis Crick to model DNA’s structure correctly. Despite the significance of her work, Franklin’s name was often omitted from the accolades, leaving her legacy in the shadows. Today, she is recognized as an unsung heroine of science whose insights reshaped molecular biology and paved the way for numerous advances in genetics and medicine.

Franklin’s story is not just about science; it is also a reflection of the historical challenges faced by women in academia and research. Her perseverance and unwavering commitment to scientific inquiry in a male-dominated field make her an inspiring figure whose contributions have finally begun to receive the acknowledgment they deserve. Her life and career serve as a beacon for aspiring scientists, particularly women, emphasizing the importance of tenacity, excellence, and breaking barriers in science.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1920 in London, Rosalind Franklin displayed an early aptitude for science and mathematics. Encouraged by her intellectually progressive family, she pursued higher education at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she studied chemistry. At a time when women faced significant barriers in scientific disciplines, Franklin excelled, earning her Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of Cambridge. Her intelligence, determination, and passion for discovery became apparent early in her academic journey, as she demonstrated an exceptional ability to grasp and analyze complex scientific problems.

Her doctoral research focused on the properties of coal and carbon structures, a field in which she made notable contributions. Her work on the porosity of coal had significant industrial applications, particularly in fuel efficiency and gas storage. She meticulously examined coal’s microstructure, providing valuable insights that improved the development of gas masks during World War II, an innovation that had life-saving implications. Additionally, her findings on carbon’s structural properties contributed to advancements in material science, influencing research in nanotechnology decades later.

Despite these achievements, Franklin sought new intellectual challenges. Her passion for uncovering the secrets of molecular structures led her to transition into biological research, setting the stage for her groundbreaking DNA studies. Her ability to meticulously analyze and interpret complex data would later prove invaluable in her contributions to DNA research. She believed that rigorous experimentation and analytical precision were essential in scientific discovery, an approach that would define her legacy.

Franklin’s move into biological research was motivated by her growing interest in understanding life at the molecular level. She joined King’s College London in 1951, bringing with her an unparalleled expertise in X-ray diffraction techniques. This transition marked the beginning of a period of groundbreaking work, as she applied her skills to the study of DNA’s structure. The application of X-ray crystallography to biological molecules was still a relatively new field, and Franklin’s pioneering work would soon prove instrumental in one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century.

Contributions to DNA Research

Franklin’s expertise in X-ray diffraction techniques led her to King’s College London in 1951, where she was tasked with studying DNA’s structure. Using advanced X-ray crystallography methods, Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling captured Photo 51, an image that revealed DNA’s helical structure with unprecedented clarity. This photograph was later shown to Watson and Crick without her direct knowledge, providing them with the key insight needed to develop their double helix model. The impact of this unauthorized sharing of her work would later spark discussions about ethics in scientific research and intellectual property.

Her meticulous data collection and analytical approach laid the groundwork for understanding DNA’s fundamental structure. Franklin’s research not only confirmed the helical nature of DNA but also provided crucial measurements of its dimensions, reinforcing the model proposed by Watson and Crick. Additionally, her careful differentiation of the two structural forms of DNA (A-form and B-form) was a critical component in piecing together the complete picture of DNA’s organization. This differentiation was essential in understanding the DNA molecule’s flexibility and function, influencing later genetic research and applications. Her precision in defining these two forms contributed to a better understanding of how DNA operates under different physiological conditions, laying the groundwork for further genetic and molecular biology studies.

Despite her contributions, Franklin was often left out of the recognition that followed the discovery. Many of her colleagues failed to acknowledge the depth of her role, and her work was, at times, used without her consent. These circumstances highlight broader issues of gender inequality in science, which persisted for decades after her time. Had she been given the credit she was due, she would likely have been included in the landmark Nobel Prize award that followed. The omission of her name from the Nobel Prize has since been viewed as one of the most glaring oversights in scientific history, prompting retrospective acknowledgments and increasing efforts to highlight the contributions of underrepresented scientists in groundbreaking discoveries. Franklin’s case has become a pivotal example in discussions about equity in science, inspiring initiatives to ensure proper attribution and recognition for all researchers, regardless of gender.

Challenges and Overlooked Recognition

Throughout her career, Franklin faced significant challenges, including gender bias, professional rivalries, and institutional limitations. As a woman working in a male-dominated research environment, she often encountered skepticism and resistance from her colleagues. Her working relationship with Maurice Wilkins, who also worked on DNA research at King’s College, was strained due to misunderstandings and a lack of proper collaboration. The hierarchical and often exclusionary nature of academic research at the time placed further obstacles in her path, limiting her access to crucial information and recognition.

In addition to professional tensions, Franklin’s work environment was less than welcoming. King’s College London was known for its conservative and male-centered culture, and Franklin was often denied the same professional courtesies and respect afforded to her male colleagues. Despite this, she persevered, producing groundbreaking work that would eventually revolutionize molecular biology.

When Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on DNA, Franklin had already passed away from ovarian cancer at the age of 37. Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously, which meant Franklin was never formally recognized for her pivotal role in unlocking the structure of life’s blueprint. However, letters and memoirs published later revealed the extent of her contributions, leading to a gradual reassessment of her role in the scientific community. Scientists and historians have since worked to correct this oversight, acknowledging her rightful place in the annals of scientific discovery. Several biographies and retrospective analyses have shed light on the gendered power dynamics that influenced her exclusion from the award and the broader recognition of her achievements. Today, Franklin’s story serves as a powerful example of the barriers women in STEM fields have historically faced and continues to inspire efforts toward inclusivity and equity in the sciences.

Legacy and Impact

Over the decades, Rosalind Franklin’s contributions have gained widespread recognition. Scientists and historians have since highlighted the indispensable role she played in DNA research. Many institutions now honor her legacy through awards, buildings, and research centers named in her memory. She has become a symbol of the challenges faced by women in STEM and an inspiration to future generations of scientists.

Franklin’s work extended beyond DNA. After leaving King’s College, she continued her research at Birkbeck College, where she made significant contributions to the study of viruses. Her work on the tobacco mosaic virus and polio virus was instrumental in understanding the structural composition of viruses, paving the way for advancements in virology and vaccine development. Her studies on molecular structures influenced later research in nanotechnology and materials science. The precision and discipline she brought to her research provided crucial insights into viral behavior, which remains fundamental in contemporary medical advancements.

Today, numerous institutions and programs have been established in her honor, including the Rosalind Franklin Institute and the Rosalind Franklin Society, both dedicated to promoting women in science and furthering research in structural biology. Schools, laboratories, and grants now bear her name, ensuring that her contributions are not forgotten. In popular culture, books, documentaries, and even films have sought to shed light on her role in DNA’s discovery, further cementing her legacy in public consciousness.

Conclusion

Rosalind Franklin was far more than a footnote in the history of DNA’s discovery—she was a brilliant scientist whose meticulous research provided the foundation for one of the greatest scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century. While she may not have received the recognition she deserved in her lifetime, her legacy continues to inspire and educate.

Her story serves as a reminder of the importance of recognizing all contributors in scientific discoveries, regardless of gender or status. As science progresses, so too does our appreciation for the contributions of those who laid the groundwork for our understanding of life at the molecular level. Rosalind Franklin’s work remains a testament to the power of curiosity, perseverance, and dedication in the pursuit of knowledge. Her name is now synonymous with excellence in structural biology, and her contributions continue to impact scientific discovery in genetics, virology, and beyond.