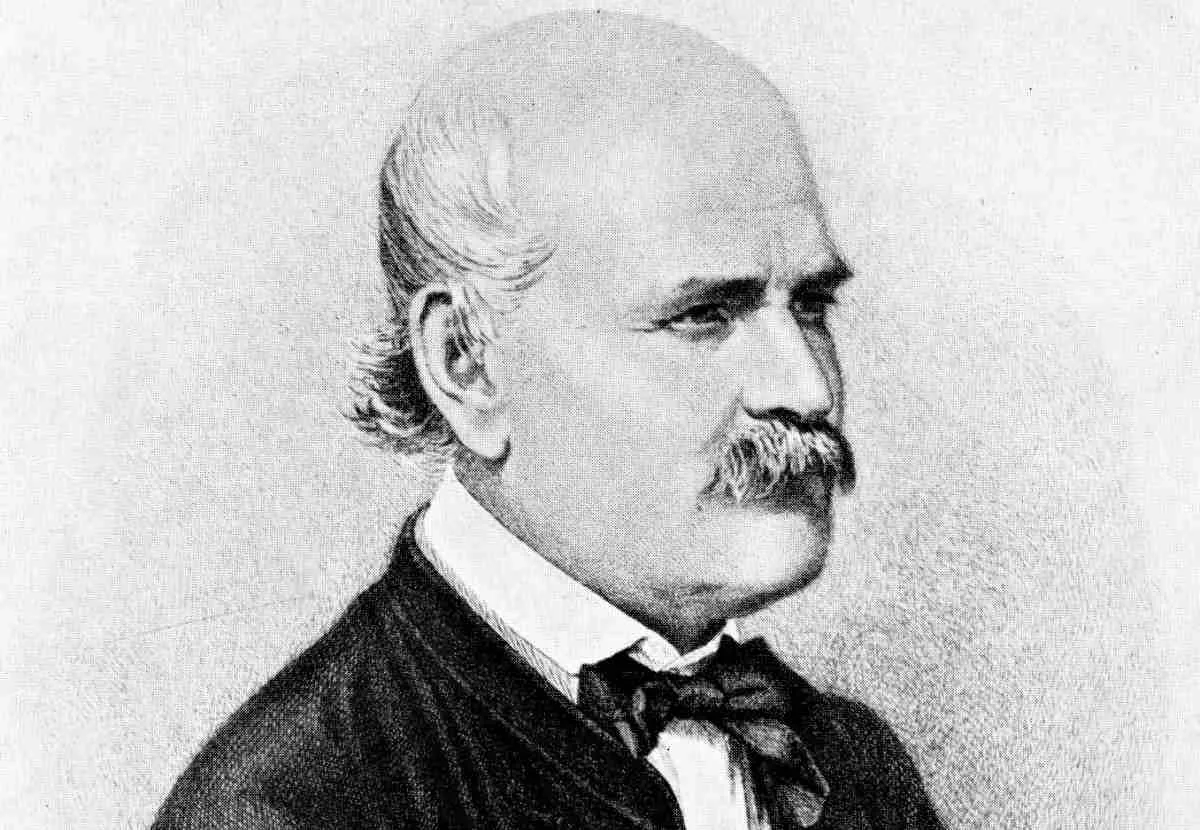

Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician in the 19th century, revolutionized medical hygiene with a simple yet groundbreaking concept: handwashing. At a time when the link between cleanliness and disease prevention was poorly understood, Semmelweis’ insistence on antiseptic practices met with resistance from the medical community. His contributions, although largely ignored during his lifetime, ultimately laid the foundation for modern antiseptic procedures and infection control. His work remains a pivotal turning point in the history of medicine, illustrating the need for scientific rigor, perseverance, and advocacy in the face of skepticism.

Semmelweis’ discoveries were born out of meticulous observation and an unwavering dedication to saving lives. Despite his revolutionary findings, he struggled to gain acceptance for his methods due to prevailing medical dogma and entrenched traditions. Many doctors of his era believed that infections were caused by imbalances in bodily humors or exposure to miasma, dismissing the role of unseen pathogens. His recommendation that physicians wash their hands before treating patients was perceived as an unnecessary burden rather than a life-saving measure.

Beyond the realm of obstetrics, Semmelweis’ principles held significant implications for the broader medical field. If properly implemented, his hygiene practices could have reduced post-surgical infections and mortality in hospitals worldwide. Yet, his findings were dismissed for decades, delaying critical progress in antiseptic procedures. His journey exemplifies the challenges faced by medical pioneers who introduce radical ideas ahead of their time, and it underscores the difficulty of changing established medical practices.

Today, Semmelweis’ name is synonymous with patient safety and preventive medicine. His struggles serve as a cautionary tale about the perils of resisting scientific evidence and the necessity of continually refining medical knowledge. As healthcare professionals champion infection control and public health initiatives, they build upon the legacy of Semmelweis, whose once-controversial ideas are now foundational to modern medical practice.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1818 in Buda, Hungary, Semmelweis displayed early academic excellence, showing a keen interest in science and medicine from a young age. His parents, recognizing his intellectual capabilities, encouraged him to pursue higher education. He enrolled at the University of Vienna in 1837, where he initially studied law before switching to medicine, drawn by his fascination with human anatomy and physiology. Semmelweis was an exceptional student, known for his sharp analytical skills and meticulous approach to research.

After earning his doctorate in 1844, he initially considered a career in surgery but ultimately chose obstetrics, a field in which he saw an urgent need for improvement, particularly in reducing maternal mortality rates. His decision was influenced by the high rates of puerperal fever, a deadly postpartum infection that afflicted many new mothers. In 1846, he was appointed as an assistant at the Vienna General Hospital’s maternity clinic, where he would make his most significant discovery. He dedicated himself to observing and analyzing the conditions within the clinic, striving to understand the underlying causes of the rampant maternal deaths. His relentless pursuit of answers led him to identify the crucial role that hygiene played in infection control, setting the stage for his groundbreaking work in medical hygiene.

The Discovery of Hand Hygiene

During his tenure at the Vienna General Hospital, Semmelweis observed a disturbing trend: the mortality rate in the clinic staffed by medical students was significantly higher than in the one run by midwives. Many women admitted to the doctor-led clinic succumbed to puerperal fever, a deadly postpartum infection. Through careful observation, he hypothesized that medical students, who frequently performed autopsies before delivering babies, were unknowingly transferring infectious material to their patients.

In 1847, Semmelweis instituted a strict policy requiring doctors and medical students to wash their hands with a chlorine solution before assisting in childbirth. The results were remarkable: maternal mortality rates dropped dramatically from over 10% to less than 2%. This simple yet effective measure demonstrated the importance of hygiene in preventing infection and became one of the earliest examples of evidence-based medicine.

Additionally, Semmelweis extended his hygiene protocols beyond obstetrics. He required that all physicians sanitize their instruments and maintain cleanliness in patient wards, further reducing infection rates across the hospital. His findings, however, remained unappreciated in a medical landscape that still attributed disease to miasma theory, the belief that illnesses were caused by “bad air” rather than microscopic organisms.

Resistance from the Medical Community

Despite his compelling findings, Semmelweis faced intense opposition from his peers. The prevailing medical beliefs of the time did not recognize germs as the cause of disease, and many doctors were unwilling to accept that they might be responsible for their patients’ deaths. His ideas challenged established medical traditions, and he faced ridicule and professional isolation.

Medical practitioners took offense at the implication that they were harming their patients. Many resisted the idea that unseen contaminants could be causing disease, and the notion that a simple practice like handwashing could significantly reduce mortality was seen as absurd. This resistance was exacerbated by Semmelweis’ sometimes confrontational approach—he openly criticized colleagues who refused to adopt his practices, which further alienated him from the medical community.

Frustrated by the resistance, Semmelweis published his findings in 1861 in The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. However, his work continued to be dismissed, and he became increasingly outspoken, even combative, in defense of his theory. His mental and emotional health deteriorated as he faced relentless opposition, and he eventually suffered a mental breakdown. In 1865, he was committed to an asylum, where he tragically died at the age of 47 from an infection—ironically, the very type of condition he had worked so hard to prevent.

Legacy and Impact

Although Semmelweis did not live to see his ideas widely accepted, his work paved the way for future advancements in medical hygiene. Decades later, the discoveries of Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister confirmed the germ theory of disease and validated Semmelweis’ handwashing protocols. Pasteur’s research into microbial life and Lister’s introduction of antiseptic surgical techniques built upon Semmelweis’ findings, fundamentally changing the practice of medicine.

Today, Semmelweis is recognized as a pioneer of antiseptic procedures, and his legacy is celebrated in medical history. His contributions have influenced modern hospital sanitation standards, the development of infection control guidelines, and routine hand hygiene protocols practiced worldwide. The Semmelweis Reflex, a term used to describe the tendency to reject new knowledge that contradicts established norms, is named in his honor and serves as a cautionary reminder of the importance of open-mindedness in scientific discovery.

In Hungary, Semmelweis is now a national hero. The Semmelweis University of Medicine in Budapest bears his name, and he is commemorated in numerous medical institutions around the world. His story is frequently taught in medical schools as an example of both scientific breakthrough and the dangers of rigid thinking within the scientific community.

Conclusion

Ignaz Semmelweis’ insistence on hand hygiene revolutionized the field of medicine, saving countless lives. Though he faced rejection during his lifetime, his contributions remain fundamental to modern infection control practices. His story serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of evidence-based medical practices and the need for persistence in the face of resistance. Semmelweis’ legacy continues to inspire healthcare professionals, reinforcing the idea that even the simplest interventions—when backed by rigorous science—can have an immeasurable impact on public health.

His work underscores the need for humility and adaptability in medicine, urging the medical community to embrace new knowledge rather than resist it. Today, hand hygiene is a cornerstone of hospital protocols, proving that Semmelweis’ discoveries were not only valid but revolutionary. His contributions remain a testament to the enduring power of scientific progress and the critical role of visionary thinkers in shaping the future of healthcare.