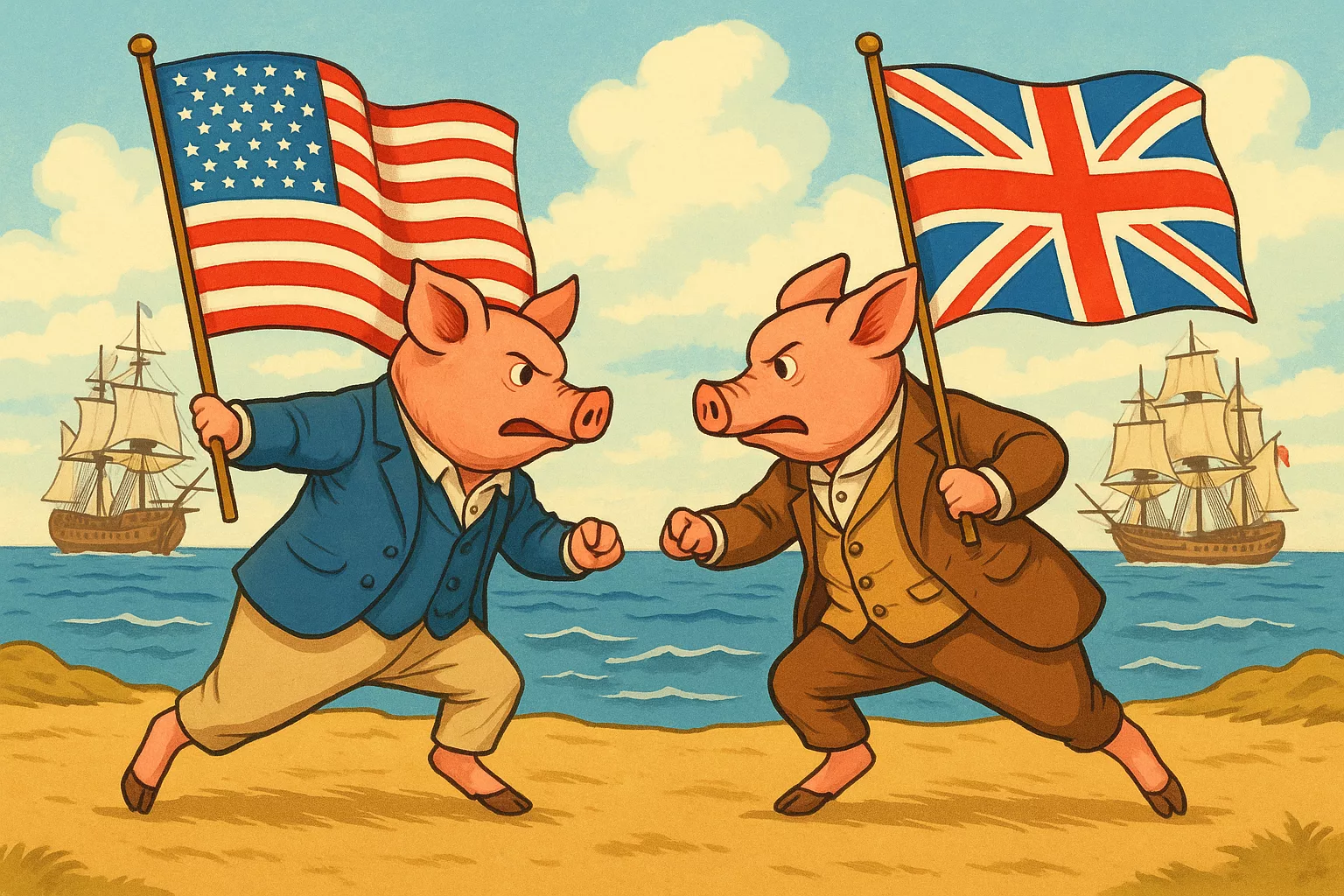

History is full of wars started over land, power, pride, and politics — but every now and then, something so absurd happens, you can’t help but laugh. One such story is the Pig War — a military standoff between two global powers, the United States and Great Britain, that nearly escalated into full-blown war in 1859 over… a pig. Yes, a literal pig.

This wasn’t some metaphor for larger tensions. This was, quite literally, about a black Berkshire boar who wandered into the wrong potato patch. What followed was months of saber-rattling, armed troops glaring across a disputed frontier, and warships looming just offshore — all sparked by a dead pig and an unclear boundary line on a map.

But this story isn’t just funny. It’s revealing. It shows how fragile peace can be, how egos can inflate misunderstandings, and how, sometimes, choosing not to fire is the most courageous thing a military can do.

San Juan Island: The Gray Zone Between Empires

To understand how a pig could come to cause an international crisis, you have to understand the setting: San Juan Island, a jewel of pine-covered hills and rocky cliffs nestled between Washington State and Vancouver Island.

The trouble began with the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which was supposed to settle the border dispute between Britain and the U.S. It declared the boundary would run “through the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island.”

Sounds clear? It wasn’t. Because there are two channels: the Haro Strait and the Rosario Strait. And right between them sits the San Juan Islands — claimed by both sides, governed by neither.

American settlers — rugged, hopeful, many newly arrived from the East — began homesteading there. Meanwhile, the powerful British Hudson’s Bay Company also set up shop, with sheep farms, trade posts, and loyal employees. The two groups coexisted awkwardly — until one pig pushed things too far.

The Pig That Crossed the Line

On June 15, 1859, Lyman Cutlar, an American farmer trying to carve out a life on the island, found a pig rooting through his garden again. It wasn’t the first time. The pig — owned by Irishman Charles Griffin, a Hudson’s Bay employee — had been helping itself to Cutlar’s potatoes repeatedly.

That day, Cutlar had enough. He shot the pig.

Soon after, Griffin confronted him. Cutlar offered to pay compensation — about $10. Griffin was furious. “It was up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig,” he reportedly said.

The British authorities backed Griffin and threatened to arrest Cutlar for destroying property. The American settlers panicked. Were they living under British rule now? They appealed to the U.S. military for protection.

When Diplomacy Breaks Down, Soldiers Show Up

Enter General William S. Harney, a brash, combative American commander known for his hatred of British interference. Upon hearing the news, Harney didn’t hesitate. He sent Captain George Pickett — a man whose name would later become infamous at Gettysburg — to the island with 66 troops and orders to prevent any British landing “at all hazards.”

Pickett raised the American flag and declared the island U.S. territory.

The British, unsurprisingly, didn’t take this lightly. Soon, three British warships were anchored offshore with over 2,000 marines at the ready. For weeks, the two militaries glared at each other, dug in, guns loaded, waiting for someone to make the first move.

It was a powder keg — with a pig-shaped fuse.

Two Superpowers, One Dead Pig, Zero Shots Fired

It’s worth pausing here to appreciate how close this came to war. A minor property dispute had spiraled into a full-blown international crisis. Soldiers stood ready. Cannons were aimed. Naval commanders were receiving conflicting orders. And all because of an animal that didn’t respect property lines.

But even as the situation grew tense, neither side wanted war. British Admiral Robert Baynes, upon arriving and assessing the situation, wisely refused to escalate. “I will not involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig,” he said.

Eventually, saner heads prevailed. Washington and London, both shocked by the escalation, scrambled to de-escalate. By fall, both governments agreed to a joint military occupation of San Juan Island until a permanent resolution could be reached.

Each nation would maintain a camp on opposite ends of the island. No more saber-rattling. No more threats. Just a shared, peaceful standoff that would last for 13 years.

Camp Life: From Near-War to Near-Friends

One of the strangest — and most charming — legacies of the Pig War is what came next. American soldiers and British marines, stationed just miles apart, developed an unexpectedly cordial relationship. They held picnics together, visited each other’s dances, shared supplies in hard winters, and even organized sporting events.

What had nearly been a war became, bizarrely, one of the most peaceful joint military occupations in modern history.

American Camp, on the southern tip, was more rugged — tents, basic barracks, military drills. English Camp, on the northern end, was elegant, with gardens and a formal parade ground. But the men got along. They respected one another. And for over a decade, they waited for a decision that only politicians and diplomats could deliver.

The Final Decision: A German Kaiser Settles the Pig War

In 1871, both nations agreed to submit the boundary dispute to international arbitration. The chosen mediator? Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany.

After reviewing the evidence and hearing arguments, the Kaiser ruled in favor of the United States. On October 21, 1872, the British peacefully withdrew, and San Juan Island officially became American territory.

There was no parade. No treaty-signing spectacle. Just the quiet end to a conflict that had, against all odds, stayed bloodless.

Why the Pig War Still Matters

Sure, it’s funny. A pig causes an international crisis? It sounds like a satire. But the Pig War teaches something valuable.

It shows how misunderstandings, left unchecked, can spiral into dangerous confrontations. It reminds us how important clear treaties and good-faith diplomacy are. And, perhaps most importantly, it offers a rare example of restraint in an era often defined by imperial ambition and bloodshed.

Both nations could have gone to war. There were certainly people who wanted to. But instead, they waited, talked, and chose peace. That may be the most remarkable part of all.

The Island Today: Peace, Parks, and Pigs Remembered

If you visit San Juan Island today, you can still walk the grounds of both American and English camps. The buildings have been preserved as part of the San Juan Island National Historical Park. There’s even a marker where Cutlar shot the pig — a strange monument to a moment that could have changed the world.

You’ll see cannons that never fired, barracks that once housed soldiers preparing for war but ending up trading recipes and marching tunes. And you’ll learn the story of how a humble pig almost became the symbol of a war that never happened — because people chose not to let it.

Final Thoughts

The Pig War is one of those stories that makes history come alive. It’s strange, funny, and a little unbelievable — but it happened. A single pig, a stubborn farmer, and a vague treaty nearly brought two nations to blows.

But in the end, no shots were fired. No lives were lost. Just a lot of potatoes, some wounded pride, and a great story left behind.

And maybe that’s the best kind of war story there is.