The Kaaba, located in the city of Mecca in modern-day Saudi Arabia, is among the most significant and recognizable religious structures in the world. It serves as the focal point of Islamic worship and is the direction, or Qibla, toward which over 1.9 billion Muslims pray daily. Beyond its central role in worship, the Kaaba is a historical and cultural symbol that has evolved over centuries, with its significance rooted in the traditions of early Arabia and the development of Islam.

The structure and its associated rituals hold both historical and spiritual importance, tying the Islamic faith to ancient traditions while underscoring themes of unity and devotion. This article explores the origins of the Kaaba, its historical evolution, and its role in the practice and identity of Islam, offering a neutral and comprehensive understanding of its significance to Muslims worldwide.

Origin of the Kaaba

The origins of the Kaaba are deeply rooted in the history and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia, a region characterized by tribal societies, diverse religious practices, and interconnected trade networks. In its earliest iterations, the Kaaba served as a sanctuary for various tribal deities, making it a prominent religious and social hub for the region. Over time, the structure evolved in significance, transitioning from a polytheistic shrine to a revered site of monotheistic worship as presented in Islamic tradition. This transformation underscores the Kaaba’s enduring role as a symbol of unity, spirituality, and cultural continuity in the Arabian Peninsula.

In Islamic tradition, the Kaaba’s construction is attributed to Prophet Abraham (Ibrahim) and his son Ishmael (Isma’il), figures central to the monotheistic narratives of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. According to Islamic belief, Abraham, guided by divine instruction, established the Kaaba as a sanctuary dedicated to the worship of a singular deity, Allah. This act of devotion, shared with his son, is seen as a cornerstone of the Abrahamic legacy. The Qur’an narrates this event with reverence, highlighting their prayer for divine acceptance as they laid the foundation of the sacred structure:

“And [mention] when Abraham and Ishmael were raising the foundations of the House [saying]: ‘Our Lord, accept [this] from us. Indeed, You are the Hearing, the Knowing.’” (Surah Al-Baqarah, 2:127)

In this context, the Kaaba is not merely a physical structure but also a profound symbol of submission, faith, and the shared spiritual heritage of humanity. Its significance in Islamic theology transcends its material presence, positioning it as a unifying axis for the worship of Allah and a testament to the timeless principles of monotheism.

The Kaaba’s association with Abraham serves as a powerful link between Islam and the broader Abrahamic traditions. While historical and archaeological evidence about its original construction remains inconclusive, the Kaaba’s role in Islamic narratives reflects an effort to root the faith within a continuum of divine revelation shared with Judaism and Christianity. This connection reinforces the Kaaba’s theological importance, presenting it as a symbol of humanity’s collective spiritual aspirations and its relationship with the Creator.

Even before its integration into Islamic practice, the Kaaba held a central place in the religious and social life of the Arabian Peninsula. Pre-Islamic Arab tribes regarded it as a sacred site, incorporating it into their polytheistic worship. The structure housed numerous idols representing various tribal deities, and annual pilgrimages to the Kaaba were a significant cultural event. These gatherings fostered economic exchanges and social cohesion, making the Kaaba a multifaceted center of activity that extended beyond its religious role.

Despite its use as a polytheistic shrine during the pre-Islamic era, certain traditions tied to the Kaaba—such as circumambulation (tawaf) and reverence for the Black Stone (Hajr al-Aswad)—persisted into Islamic rituals, albeit with reinterpreted meanings. This continuity of practice highlights the Kaaba’s enduring significance as a sacred structure and its ability to adapt to shifting religious paradigms.

Pre-Islamic Kaaba: A Polytheistic Sanctuary

Before the emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE, the Kaaba was already a significant religious and cultural center in the Arabian Peninsula, deeply embedded in the lives and traditions of the region’s diverse tribal societies. Situated in the city of Mecca, the Kaaba served as a sanctuary for polytheistic worship, housing numerous idols and sacred objects associated with the deities revered by various tribes. This shared spiritual site played a crucial role in fostering both religious expression and intertribal cohesion in an otherwise politically and socially fragmented landscape.

The Kaaba was central to the polytheistic practices of pre-Islamic Arabia, accommodating a pantheon of deities that reflected the beliefs and customs of the peninsula’s tribes. Among the most prominent idols housed within the Kaaba were Hubal, regarded as a chief deity by the Quraysh tribe; Al-Lat, a goddess associated with fertility and war; Al-Uzza, linked to power and protection; and Manat, the goddess of fate. These deities represented a variety of natural and supernatural forces, reflecting the diverse spiritual needs and traditions of the region. It is estimated that the Kaaba contained as many as 360 idols, symbolizing its status as a central shrine for the tribes of Arabia.

The city of Mecca, which grew around the Kaaba, became an important cultural and economic hub during the pre-Islamic era. Its strategic location at the crossroads of trade routes connecting Yemen, the Levant, and Mesopotamia made it a vital center for commerce. Pilgrimage to the Kaaba, known as Hajj even in pre-Islamic times, contributed significantly to Mecca’s prosperity. Tribes from across the Arabian Peninsula would travel to Mecca during designated months of peace, ensuring safe passage for pilgrims and traders alike. These gatherings created opportunities for economic exchange, social interaction, and the negotiation of intertribal alliances, further solidifying the Kaaba’s role as a unifying focal point.

Although polytheistic practices dominated, certain traditions associated with the Kaaba hint at its earlier monotheistic origins, as suggested by Islamic tradition. For instance, the act of circumambulation (tawaf)—walking around the Kaaba in a clockwise direction—was a ritual performed by pre-Islamic pilgrims. Similarly, the Black Stone (Hajr al-Aswad), embedded in the Kaaba’s eastern corner, was venerated as a sacred object, although its exact significance varied among tribes.

These practices persisted into the Islamic era, where they were reinterpreted within the framework of monotheism. Islam maintained the act of circumambulation and the veneration of the Black Stone, reframing them as expressions of devotion to Allah rather than elements of polytheistic worship. This continuity of ritual highlights the adaptive nature of the Kaaba’s traditions, which allowed it to remain a central religious site even as the spiritual landscape of Arabia transformed with the rise of Islam.

The Kaaba in the Islamic Era

The transformation of the Kaaba from a polytheistic shrine to the central religious site of Islam occurred during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad and marked a pivotal moment in the history of the Arabian Peninsula.

The Role of the Kaaba in Muhammad’s Early Life

Born into the Quraysh tribe, which managed the Kaaba, Muhammad grew up in Mecca and would have been familiar with the site’s religious and social significance. A well-known episode in his early life involved resolving a dispute among Meccan leaders over the placement of the Black Stone during a reconstruction of the Kaaba. His wisdom in resolving the issue earned him respect and highlighted the Kaaba’s role as a symbol of communal authority and cohesion.

Reclamation of the Kaaba

The Kaaba’s reclamation as a monotheistic sanctuary occurred after Muhammad’s conquest of Mecca in 630 CE. Upon entering the city, Muhammad ordered the removal of idols from the Kaaba, reestablishing it as a site dedicated solely to the worship of Allah. The act symbolized the triumph of monotheism over polytheism and reinforced the Kaaba’s centrality in Islamic worship.

This reclamation also established the Kaaba as the Qibla, the direction toward which Muslims pray. Initially, early Muslims had faced Jerusalem during prayer, but the Qibla was later redirected to the Kaaba, signifying a distinct Islamic identity.

The Physical Structure of the Kaaba

The Kaaba has undergone numerous reconstructions and renovations over the centuries, adapting to environmental and social changes while maintaining its core dimensions and symbolism.

Description and Key Features

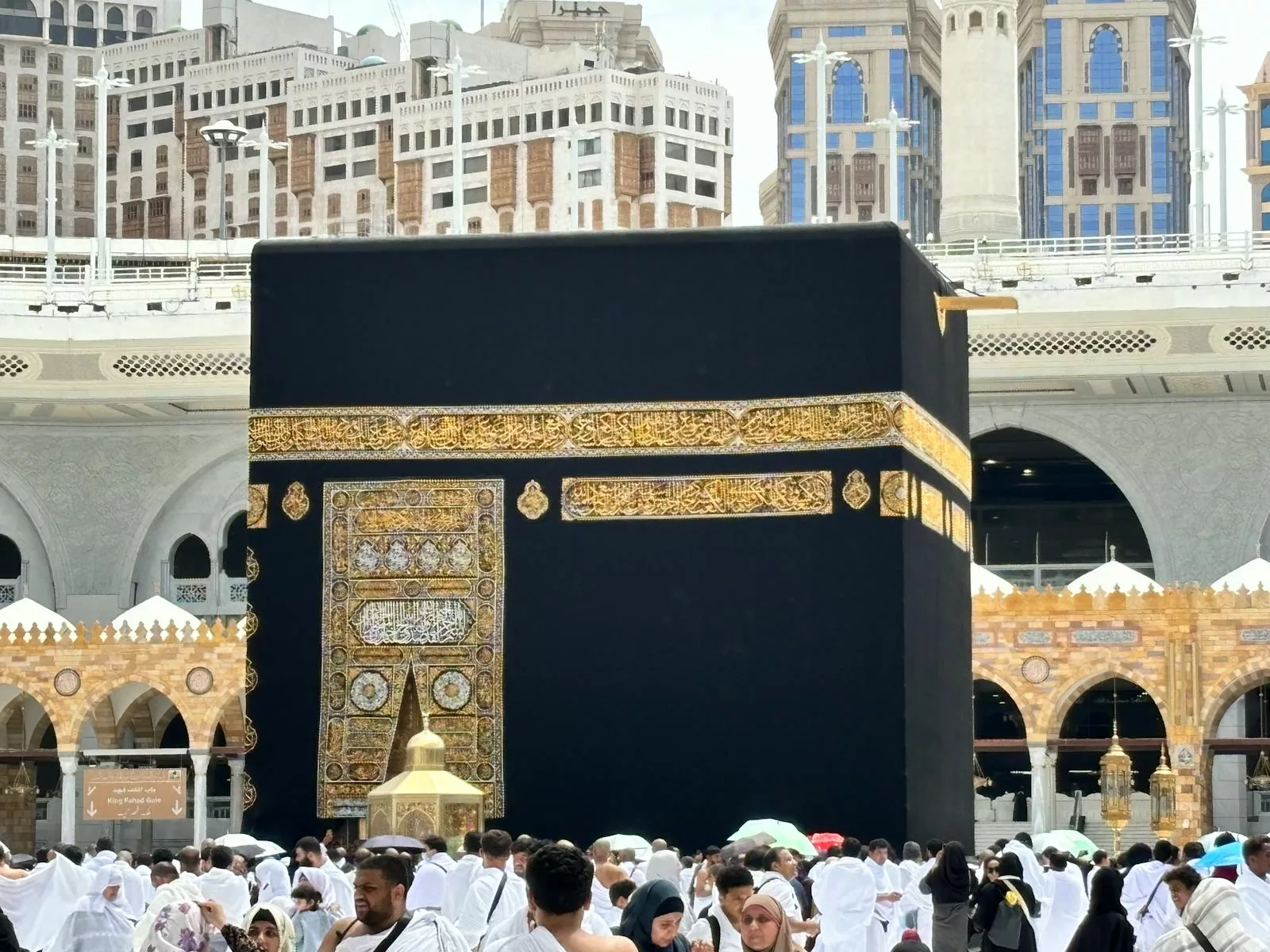

The Kaaba is a cuboid structure made of granite, measuring approximately 15 meters high and 10.5 meters on its shorter side. Its simple yet imposing design emphasizes function over ornamentation, reflecting its spiritual purpose.

Key features of the Kaaba include:

- Hajr al-Aswad (Black Stone): A dark, polished stone set into the eastern corner, believed by Islamic tradition to date back to the time of Abraham. Pilgrims often touch or kiss the stone during the Hajj pilgrimage.

- Kiswah: The black silk cloth covering the Kaaba, embroidered with Quranic verses in gold thread. The Kiswah is replaced annually during Hajj.

- Hijr Ismail: A semi-circular wall adjacent to the Kaaba, marking an area traditionally associated with Ishmael and his mother Hagar.

- Mizab al-Rahma: A golden spout on the roof for rainwater drainage.

These elements underscore the Kaaba’s unique combination of historical, religious, and architectural significance.

The Kaaba’s Religious Significance

Qibla: The Direction of Prayer

The Kaaba serves as the Qibla, the direction toward which Muslims around the world face during their five daily prayers (Salah). This practice emphasizes the unity of the global Muslim community (Ummah) and symbolizes submission to Allah.

The choice of a single direction for prayer reinforces a sense of equality and collective worship, connecting individuals across cultures and continents.

The Centerpiece of Hajj

The Kaaba is the focal point of the Hajj, an annual pilgrimage required of all able Muslims at least once in their lifetime. During Hajj, pilgrims perform rituals such as tawaf, the act of circumambulating the Kaaba seven times, symbolizing devotion and the unifying orbit of humanity around God.

The Kaaba’s centrality during Hajj reflects its role as a physical and spiritual anchor for Islam, drawing millions of people from diverse backgrounds together in a shared act of worship.

Historical and Cultural Adaptations

Custodianship and Maintenance

The Kaaba’s custodianship has historically been a source of prestige and responsibility. The Sons of Shaybah, descendants of the Quraysh tribe, are the traditional custodians, overseeing its upkeep and rituals. Modern Saudi authorities have invested heavily in the maintenance and expansion of the surrounding Masjid al-Haram to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims.

Modern Context

Advances in technology and infrastructure have made the Kaaba more accessible to Muslims worldwide. Live broadcasts of prayers and Hajj rituals allow those unable to travel to Mecca to feel connected to the site. Additionally, ongoing renovations ensure that the Kaaba remains a central and functional space for worship.

The Kaaba’s significance transcends its physical structure, serving as a profound symbol of faith, unity, and devotion for Muslims worldwide. From its origins in Abrahamic tradition to its role in contemporary Islamic worship, the Kaaba is a testament to the enduring power of spirituality and the shared heritage of humanity. Its centrality in the rituals and identity of Islam ensures its continued relevance, making it one of the most cherished and respected sites in the world.