Chlamydia has a reputation for being both common and quiet—often present without announcing itself. I’ve met countless patients who felt perfectly fine and were shocked when a routine test came back positive. Others only found out after a partner tested positive. Understanding how this infection behaves, how it’s diagnosed, and how it’s treated removes a lot of the fear and confusion, and it helps people navigate real decisions about health, pregnancy, and relationships with much more clarity.

What Chlamydia Is—and Why It Behaves the Way It Does

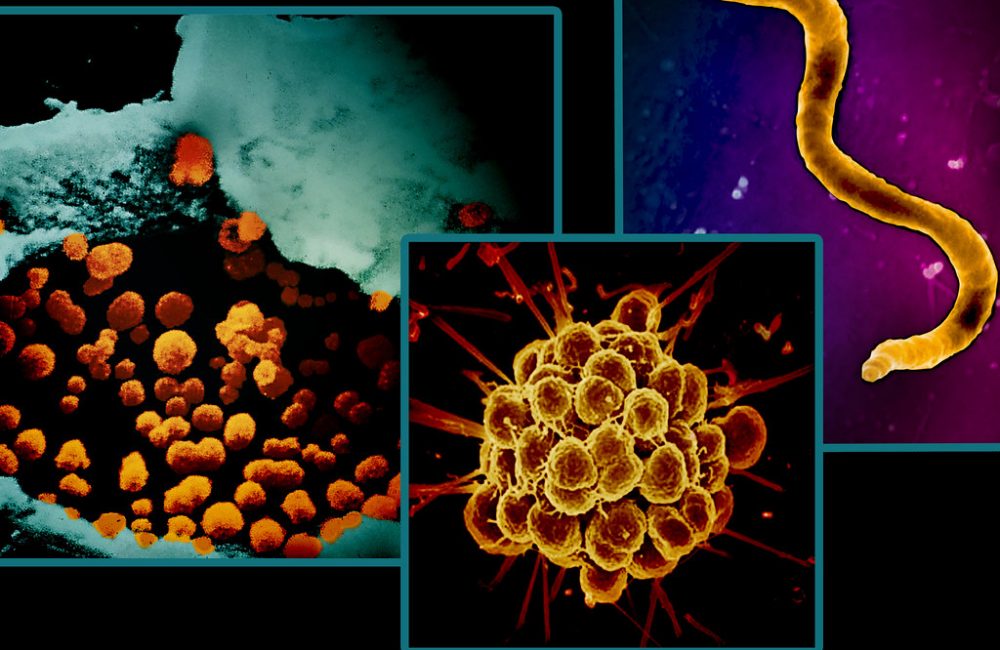

Chlamydia trachomatis is a bacteria with a unique lifecycle. It lives inside human cells, cycling between an infectious form (elementary body) and a replicating form (reticulate body). That intracellular lifestyle is part of why it can be so stealthy, and why antibiotics targeting protein synthesis—like doxycycline—are so effective.

Serovars of Chlamydia

There are different groups (serovars) of C. trachomatis:

- A–C: Cause trachoma, an eye infection and a major cause of blindness in some parts of the world.

- D–K: Cause most urogenital and rectal infections, and are the ones people typically mean when they say “chlamydia.”

- L1–L3: Cause lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), a more invasive infection that can lead to painful proctocolitis and swollen lymph nodes.

Chlamydia is a bacterial STI, not a virus. It doesn’t establish lifelong infection in the way herpes or HIV can. With the right antibiotic, it clears. The trouble is what happens when it lingers: inflammation, scarring, and complications—especially in the reproductive tract—are the downstream risks that clinicians watch closely.

How It Spreads

Transmission occurs through sexual contact: vaginal, anal, or oral sex. The bacteria can infect the cervix, urethra, rectum, and throat; it can also be passed to a newborn during delivery, infecting the eyes or lungs. Casual contact (toilet seats, shared utensils, hugging) doesn’t spread chlamydia, and it doesn’t survive well outside the body.

Key Realities of Chlamydia Transmission

- Asymptomatic Infections: Many estimates suggest that at least half of infections have no noticeable symptoms.

- Incubation Period: Usually about 1–3 weeks after exposure, though some people don’t notice symptoms at all.

- Reinfection: Common when partners aren’t treated at the same time. In clinics, it’s routine to see someone clear the infection, feel relieved, then test positive again a few months later because a partner was never treated or there was a new exposure within the same network.

Who is Most Affected: The Numbers and Patterns

Chlamydia is one of the most frequently reported bacterial STIs worldwide. To put scope to the story:

- Global Estimates: The World Health Organization estimates roughly 129 million new chlamydia infections each year among adults.

- United States: Chlamydia has been the most commonly reported bacterial STI for years, with over 1.6 million cases reported annually.

High-Risk Groups

The concentration is highest in:

- Adolescents and Young Adults: Especially people under 25.

- Communities with Limited Access to Screening and Treatment Services.

- Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): Particularly for rectal infections.

- Populations Facing Structural Inequities: Higher reported rates often appear in Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and some Hispanic/Latino communities in the U.S. Those patterns reflect systemic barriers and under-resourcing more than individual behavior differences.

Health systems influence these numbers. Where screening programs are robust and stigma is lower, more infections are identified and treated earlier. Where services are limited, infections simmer quietly longer and complications are more likely.

Symptoms: What People Notice—and What They Often Don’t

Chlamydia is famous for silence, but when symptoms show up, they tend to follow the site of infection.

Cervix and Uterus (Cervicitis, Pelvic Inflammatory Disease)

- Abnormal Vaginal Discharge: Often more than usual, sometimes with a mucopurulent quality.

- Bleeding: After sex or between periods.

- Pain with Sex.

- Pelvic or Lower Abdominal Pain: If the infection ascends.

- Burning with Urination: Overlap with urethral involvement.

- On Exam: The cervix may bleed easily with swabbing, and discharge from the cervical os can be obvious.

Untreated cervical infections can move upward to the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries—what clinicians call pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID ranges from subtle pelvic aching to severe pain with fever and tenderness. Some people with PID feel just “off” with mild cramping and spotting; others are doubled over with pain. Either can lead to scarring.

Urethra (Urethritis)

- Burning or Stinging with Urination.

- Clear to Cloudy Discharge from the Urethra.

- Itching or Irritation at the Tip of the Penis.

- Occasionally Testicular Aching: If inflammation reaches the epididymis.

Many men with urethral chlamydia have minimal symptoms or mistake them for a transient irritation. Discharge tends to be lighter than with gonorrhea, but that’s not a reliable way to distinguish.

Rectum (Proctitis)

- Rectal Discomfort, Pain, or Fullness.

- Discharge, Mucus, or Bleeding from the Rectum.

- Tenesmus: Feeling an urge to have a bowel movement even when the rectum is empty.

Rectal infections are common among people who have receptive anal sex and are frequently asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, it’s easy for people to attribute them to hemorrhoids or dietary issues, which delays testing.

If the strain is L1–L3 (LGV), symptoms can be more severe: marked rectal pain, fever, and tender lymph nodes. LGV proctocolitis can be mistaken for inflammatory bowel disease on endoscopy.

Throat (Pharynx)

- Usually Asymptomatic.

- Occasional Sore Throat.

Pharyngeal chlamydia is less common and less likely to be detected unless testing is specifically directed there.

Eyes (Conjunctiva)

- Red, Irritated, Sticky Eyes with Discharge.

- Autoinoculation: Transferring bacteria from the genital area to the eye or during birth in newborns.

Newborns

- Conjunctivitis: Shows up 5–12 days after birth.

- Pneumonia: Typically presents at 1–3 months old with a staccato cough and sometimes low-grade fever.

In neonatal pneumonia from chlamydia, oxygen levels can stay fairly normal despite persistent cough, which is one clinical clue.

Complications and Long-Term Risks

The biggest worry with chlamydia is damage from silent, ongoing inflammation.

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID): An estimated 10–15% of women with untreated chlamydial cervical infections develop PID. Repeated infections raise the risk significantly.

- Infertility: Scarring in the fallopian tubes can prevent fertilization or implantation. The risk rises with each episode of PID.

- Ectopic Pregnancy: A fertilized egg can implant in a scarred fallopian tube, a dangerous emergency.

- Chronic Pelvic Pain: Adhesions and ongoing inflammation can leave lasting pain.

- Epididymitis in Men: Pain and swelling in the epididymis; infertility from chlamydia alone is less common but inflammation can impair sperm function.

- Reactive Arthritis: A joint inflammation that can follow urethritis. The classic triad—arthritis, conjunctivitis, urethritis—still appears under the eponym Reiter’s syndrome in older literature. It’s relatively rare but well documented.

- Perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis Syndrome): Inflammation of the liver capsule causing sharp right upper quadrant pain, usually in the context of PID.

- Increased Susceptibility to HIV: Genital inflammation increases both the risk of acquiring HIV and transmitting it.

Clinically, what raises alarms is not one mild episode, but repeated reinfections. I’ve cared for patients who never felt sick yet faced ectopic pregnancies in their twenties. The pattern was subtle: college years with occasional unprotected encounters, a couple of positive tests years apart, incomplete partner treatment, and no severe episodes. The scarring accumulated without drama.

Chlamydia and Pregnancy

Chlamydia during pregnancy is a double concern—maternal complications and neonatal infection. Untreated infections are associated with:

- Premature Rupture of Membranes and Preterm Birth.

- Low Birth Weight: In some studies.

- Postpartum Infections.

- Neonatal Conjunctivitis and Pneumonia.

Standard prenatal care in many countries includes screening for chlamydia at the first prenatal visit and repeating later in pregnancy for those at higher risk. Diagnosis is via nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), the same technology used outside pregnancy.

Treatment during pregnancy is effective and safe. Azithromycin (a single dose) is commonly used in pregnancy, with amoxicillin as an alternative. After therapy, clinicians do a “test of cure” a few weeks later in pregnancy to confirm eradication and also recheck later to catch reinfection.

Newborns exposed to chlamydia during delivery can develop:

- Conjunctivitis: Swelling, redness, and discharge starting in the first couple of weeks of life.

- Pneumonia: Persistent cough and tachypnea with minimal fever around 1–3 months of age.

Neonatal treatment regimens typically include macrolide antibiotics, often erythromycin or azithromycin, dosed by weight and given for a defined period. Close follow-up is routine because symptom resolution can lag, and the doses are tailored carefully to minimize side effects in infants.

Testing and Diagnosis: How Clinicians Find It

Modern testing has dramatically improved detection. NAATs (nucleic acid amplification tests) are the gold standard because they’re highly sensitive and specific.

Common Specimen Types

- Vaginal Swab: Often the most sensitive sample for people with a cervix.

- First-Catch Urine: Commonly used, especially for men.

- Endocervical Swab: Traditional but not required when vaginal swabs are available.

- Rectal Swab: Important when there’s receptive anal exposure or rectal symptoms.

- Throat Swab: Considered when there’s receptive oral exposure; yield is lower but testing catches infections missed elsewhere.

Self-collected vaginal and rectal swabs, when instructions are followed, perform as well as clinician-collected samples. For busy clinics and for people who prefer privacy, that has been a quiet revolution; it’s far less awkward and faster.

Timing and Window Period

The incubation period is usually around 1–3 weeks, and testing too soon after exposure can miss an infection that hasn’t reached detectable levels. When clinicians evaluate someone after a recent exposure, they often combine testing with empiric treatment if follow-up is at risk or if symptoms are suggestive. That approach balances the risk of overtreating a few to prevent complications and transmission.

Retesting is not the same as a test-of-cure. Outside of pregnancy and special situations (like persistent symptoms or rectal LGV), most people don’t need a test-of-cure. Instead, guidelines encourage retesting roughly three months after treatment to catch reinfections, which are common.

Co-testing for other STIs (gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV) often happens at the same time because sexual networks and risk factors overlap. For rectal or pharyngeal exposures, clinicians request site-specific testing rather than relying solely on urine.

Differential Diagnosis: What Else Could It Be?

Symptoms overlap significantly with other infections and noninfectious conditions:

- Gonorrhea: Often more purulent discharge, but not reliably distinguishable by exam alone.

- Mycoplasma genitalium: Can cause persistent urethritis/cervicitis; requires different antibiotics in some cases.

- Trichomonas vaginalis: Frothy discharge; microscopy or NAAT confirms.

- Bacterial Vaginosis: Fishy odor, thin discharge; not an STI but can coexist.

- Herpes Simplex Virus: Painful ulcers; can cause urethritis.

- Urinary Tract Infections: Dysuria, urgency; urine culture helps differentiate.

- Hemorrhoids, Fissures, or Inflammatory Bowel Disease: For rectal symptoms.

Because of this overlap, lab confirmation is crucial. It prevents misdiagnosis and unnecessary antibiotics.

Treatment That Works: Current Regimens and What to Expect

Antibiotic therapy is straightforward but not one-size-fits-all. The success of treatment depends on the site of infection, co-infections, and whether partners are treated.

Preferred Treatment

For adolescents and adults with uncomplicated urogenital or rectal chlamydia, many guidelines now prefer:

- Doxycycline 100 mg by mouth twice daily for 7 days

Why doxycycline? Clinical data show it outperforms azithromycin for rectal chlamydia and performs at least as well for urogenital infection. Cure rates with doxycycline are typically well over 95% in non-LGV infections.

Alternatives

Alternatives include:

- Azithromycin 1 gram by mouth as a single dose

- Levofloxacin 500 mg by mouth once daily for 7 days

Azithromycin remains useful in specific situations—intolerance to doxycycline, concerns about adherence to a 7-day course, or pregnancy (where azithromycin is a go-to). However, for rectal infections in particular, azithromycin has had higher failure rates in randomized trials.

Treatment in Pregnancy

- Azithromycin 1 gram single dose: Widely used in pregnancy.

- Amoxicillin: An alternative when macrolides aren’t suitable.

- Test-of-Cure: Done 4 weeks after completing therapy in pregnancy, with retesting later to catch reinfection.

Treatment for LGV (L1–L3 Serovars)

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 21 days

- Additional Evaluation: May be needed for complications like strictures or fistulas in chronic cases.

Pelvic inflammatory disease requires broader coverage and longer treatment, often a combination regimen (for example, a cephalosporin injection plus doxycycline and metronidazole for 14 days) to cover likely organisms, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and anaerobes.

What Influences Treatment Success

- Adherence: Completing the full course drives cure rates. Inconsistent dosing opens the door to persistence.

- Site of Infection: Rectal chlamydia is where doxycycline’s advantage over azithromycin is most pronounced.

- Reinfection: Many “treatment failures” aren’t resistance—they’re new exposures from untreated partners.

- Drug Interactions and Side Effects: Doxycycline can cause photosensitivity and gastric irritation. Antacids, iron, and calcium supplements taken close to dosing can reduce absorption. Azithromycin can provoke GI upset in some people. Fluoroquinolones like levofloxacin carry rare but significant risks (tendinopathy) and are reserved for specific scenarios.

- Resistance: Classic antibiotic resistance in C. trachomatis remains relatively uncommon compared with some other bacteria. What we sometimes see described as “persistence” is more about the organism entering a less metabolically active state under stress. Clinically, the bigger problem is reinfection and under-treatment of rectal disease with single-dose regimens.

Sexual Activity and Transmission Post-Treatment

Clinical guidelines generally advise avoiding sexual activity for seven days after starting therapy and until all partners are treated. That’s not moralizing; it’s math. Antibiotics need time to work, and partners who remain untreated create a rapid ping-pong effect.

Partner Management and Reinfection Dynamics

Chlamydia is a team sport. When one person tests positive, the clinical focus expands to the network. Reinfection within a few months is common when partners aren’t treated concurrently.

A practical public health tool, where allowed, is Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT): providing medication or prescriptions to the patient for their partners without a clinical exam of those partners. EPT reduces the risk of reinfection and has been adopted in many U.S. states for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Its legality varies by region, and it’s typically supported by clear written information for partners about the medication and the importance of full evaluation for other STIs.

Retesting around three months after treatment is a standard way systems catch reinfections. In real life, it fits the typical pattern of social and sexual connections—enough time for treatment, reconnection, and the possibility of new exposures.

Misconceptions That Cause Trouble

A few persistent myths keep chlamydia circulating and complicate care:

- “No symptoms means no infection.” In clinics, the opposite is routine: no symptoms and a positive test. Silent infections cause most of the transmission and many of the complications.

- “A negative urine test covers everything.” Urine NAATs are great for urethral disease but miss rectal or cervical infections if those sites aren’t tested, especially in people with a cervix where a vaginal swab often performs better than urine.

- “You can get chlamydia from a toilet seat.” The bacteria do not survive well on surfaces and require intimate contact to transmit.

- “Natural remedies can clear it.” Herbal or over-the-counter products won’t eradicate an intracellular bacterial infection. Antibiotics with proven intracellular activity are necessary to prevent complications.

- “Antibiotics ruin birth control.” Commonly used antibiotics for chlamydia, like doxycycline and azithromycin, do not reduce the effectiveness of combined oral contraceptives in typical use. Severe vomiting or diarrhea can reduce pill absorption, which is a different issue.

- “Once treated, it’s gone forever.” Treatment clears the current infection. There’s no immunity; reinfection is easy without partner treatment or changes in exposure.

Special Clinical Situations Clinicians Watch For

Rectal Chlamydia in Cisgender Women

Rectal infection is not limited to anal intercourse. Autoinoculation and unrecognized exposures happen, and the rectum can be a reservoir that keeps cervical disease simmering. Studies find rectal chlamydia in a substantial minority of women with cervical infection,